A masterful book discussing regional deforestation and the historical context

Updated by Kotaro Nagasawa on May 06, 2025, 9:59 AM JST

Kotaro NAGASAWA

(Platinum Initiative Network, Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1958. (Engaged in research on infrastructure and social security at Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. During his first few years with the company, he was involved in projects related to flood control, and was trained by many experts on river systems at the time to think about the national land on a 100- to 1,000-year scale. He is currently an advisor to Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. He is also an auditor of Jumonji Gakuen Educational Corporation and a part-time lecturer at Tokyo City University. Coauthor of "Introduction to Infrastructure," "New Strategies from the Common Domain," and "Forty Years After Retirement. D. in Engineering.

We have learned that when forests are over-forested, the water retention capacity of mountain areas is reduced and large amounts of sediment flow down, forming overhead rivers and damaging the depth of harbors at the mouths of rivers. Therefore, they also recognize that forests should be preserved for disaster prevention. On the other hand, it is not often that we think about the reasons why deforestation leads to massive sediment runoff, or why deforestation occurs in the first place.

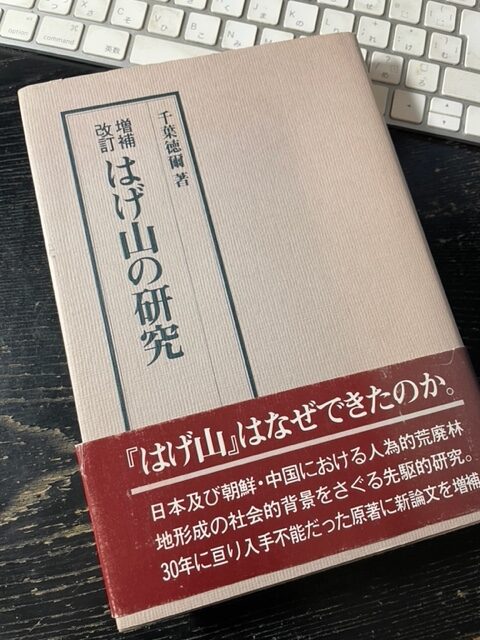

The author of this book, Mr. Tokuji Chiba (hereinafter referred to as "the author"), is the person who tackled this issue head-on, wrote a thesis on it, and obtained a doctoral degree. The book, "A Study of Bald Mountains" (hereafter referred to as "this book"), is a rewrite of the book in an easy-to-understand format for the general public. I first encountered this book in 1983. Forty-odd years later, when the "Forest Circular Economy" website was launched and I was asked to write a column, my first thought was to introduce this book.

The first part shows the distribution of bald hills throughout Japan. The first part shows the distribution of bald hills across the country, including the Inland Sea coast, the Kinki region, and the Nobi Plain, the fact that most bald hills appeared in the late 17th and early 19th centuries, and the various arguments about the causes of such extreme forest devastation. The author states that he conducted his research based on the assumption that, given the climatic characteristics of Japan, it is highly likely that these bald hills could not have occurred spontaneously, and that some form of human intervention was definitely responsible for their occurrence. The author also points out, based on the data, that forests owned by members are more likely to become bald hills than forests owned by private individuals.

Part II takes several localities as examples and examines the human activities that have led to the extreme devastation of mountain forests in each region. The following is an introduction from Part II.

Although soil erosion to the point of causing flood damage is not something that happens easily with ordinary tree cutting, it is known that if the roots of the trees, or tree roots, are excavated, the soil becomes extremely loose, causing severe soil erosion and making it easier for bald hills to form.

In the early modern period, when many bald hills occurred in Japan, there were many "osho" (a written warning against digging up the roots of trees) issued in various regions of Japan. This means that the shogunate and the various clans were probably aware that digging up tree roots was actively conducted and was causing forest devastation and flood damage.

The primary uses of tree roots are for attaching trees and for lighting. Lighting by pine roots is known for its high luminous intensity (very bright). The peasants must have needed strong lighting for some reason.

Wasn't it night work? The author focuses on a large-scale survey of the rural economy conducted by the shogunate and the Keian Gosho (1649), which was based on the results of the survey. Indeed, the document includes such phrases as, "The farmers should get up in the morning and cut the grass in the morning, work on cultivating the fields in the daytime, and in the evening, they should make ropes and knit bales, and do whatever they have to do without any interruptions," and "Men should work on their crops, women should work on their hats, and both spouses should work at night.

The book goes on to describe the poverty of farmers in those days from the ancient records of Okayama and Kanazawa. The book then points out that the traditional medieval concept of status had changed, and the large, self-sufficient family farmers were dissolved, leading to an increase in the number of small-scale farmers and their rapid integration into the commodity economy. In fact, a decree issued by the shogunate in 1642 required farmers to refrain from producing udon, soba, somen, kirimochi, manju, tofu, etc., and it is known that such processed foods were widely available in farming villages.

Under these changes, subsistence-type production by small-scale farmers gradually collapsed, leading to increased debt for commodity purchases and delays in annual tribute payments (so the shogunate instructed). Poor farmers were forced to work at night, and the digging up of tree roots in the enrollment areas in search of lighting spread. This, the book suggests, may have led to the collapse of large forest areas.

Bald mountains are widely distributed in the coastal areas of Okayama Prefecture, and it was commonly believed that this was caused by the salt manufacturing industry that flourished in the Seto Inland Sea region, which cut down forests to obtain fuel.

The author questions this common belief. The reason is that by the end of the Edo period, most of the salt manufacturing business had been converted to coal kilns, but this did not stop the degradation of the forest lands. On the contrary, the riverbed of the Jingang River has been rising ever higher since that time. There must be a cause other than the salt manufacturing industry for the degradation of forest lands in the form of bald hills.

With these hypotheses in mind, we traced the actual situation of fuel procurement in the salt manufacturing industry, and confirmed that the salt manufacturing industry in the Seto Inland Sea region, which had already become a large-scale industry in the Edo period, did not seek fuelwood and coal supplies from forest lands where yields were unstable, but rather exclusively from private forests based on contracts. The private forests are well managed and have not fallen into disrepair. On the other hand, since the bald hills are all common forests, it is difficult to attribute the cause of the destruction of the bald hill-type forests in this area to fuel logging for the salt industry, the report states.

So what were the reasons for the devastation of the forest lands in which they were enrolled?

In the area corresponding to present-day Okayama City and surrounding areas, firewood shortages were severe from the early Edo period, and firewood was brought in by ship from the Hiroshima area and Sakushu (present-day inland Okayama Prefecture). Firewood from Hiroshima became less likely to enter Okayama as the salt manufacturing industry developed in the coastal areas of the Seto Inland Sea and firewood could be sold at higher prices. Because firewood in Okayama City was priced at the official rate, firewood brought by riverboat from Mimasaka also went outside Okayama in search of more lucrative buyers. In other words, the development of the salt manufacturing industry in the entire Seto Inland Sea coastal area was also depriving coastal residents of firewood as fuel for their homes.

The poor residents were forced to collect fuel from the forest lands for their own use and for sale, a situation that could be described as plundering and led to the development of many bald hills. =The book describes the situation as follows.Continued in Part 2(Kotaro Nagasawa, Director, Platinum Network)