The Shogunate's Challenges and Failures in Aiming for a Nationally Unified Forestry Administration

Updated by Kotaro Nagasawa on June 27, 2025, 3:28 PM JST

Kotaro NAGASAWA

(Platinum Initiative Network, Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1958. (Engaged in research on infrastructure and social security at Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. During his first few years with the company, he was involved in projects related to flood control, and was trained by many experts on river systems at the time to think about the national land on a 100- to 1,000-year scale. He is currently an advisor to Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. He is also an auditor of Jumonji Gakuen Educational Corporation and a part-time lecturer at Tokyo City University. Coauthor of "Introduction to Infrastructure," "New Strategies from the Common Domain," and "Forty Years After Retirement. D. in Engineering.

*Click here for the first part.

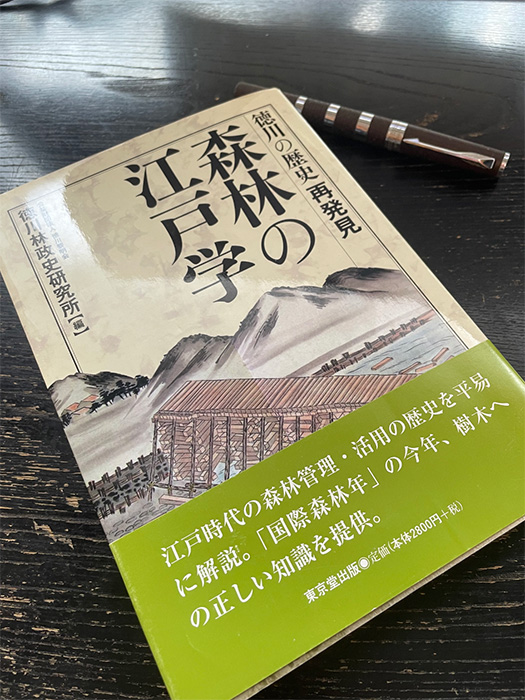

Distribution Control by Edo Imperial Procurement Merchants Blows to Local Forest Resources: Reading "Edo Studies of Forests" by Tokugawa Forestry History Institute (Part 1)

In the previous issue, I wrote about the importance of local governments (clans) pursuing, compiling, and sharing afforestation techniques suited to their regions in the nationwide revival of forestry in the latter half of the Edo period. It seems that the Edo shogunate of the time was not inept, but standardizing agriculture and forestry, which are rooted in local climates, across the country was quite a difficult undertaking. Here are two examples introduced in this book.

A shogunate account official, while traveling between Edo and Nagasaki, took note of the cedar cutting technique that had spread from southern Kyushu to northern Kyushu. In Nagasaki, this technique was promoted as "planting by house," whereby two cuttings were taken from each house every spring and fall, and those that did not take root were replanted several times from the original source to grow into mature trees. The magistrate planned to spread this method throughout the country and had his subordinates learn it, leading to the issuance of an edict that it be applied in all shogunate territories throughout the country.

The nunbunshi included detailed instructions on when to take cuttings, how to make cuttings, how to take cuttings, how to water the cuttings, and the intervals between cuttings. The number of cuttings taken and how well they took root were required to be reported to the shogunate. Twelve years later, however, the shogunate acknowledged the failure of the cutting project, stating that "no progress has been made. The author explains that the appropriate method of forestation varied from region to region, and that it was not something that could be dealt with by a uniform national law.

The other is the case of bureaucrats in the early Meiji period who tried to introduce German forestry to Japan. From its inception, the Meiji government sent some bureaucrats to Europe to learn about technologies and policies for modernization. Among them, influenced by German forestry, some bureaucrats in the Home Affairs Bureau began to advocate the establishment of direct control over the nation's official forests (government-owned forests) to strengthen state management.

The Ministry of the Interior promoted a policy known as "domestic reproduction" with the two main objectives of government forest management being the maintenance of safety forest functions and the production of good timber. A typical example of this policy is the "harvesting of trees and fruits" that began around 1880 (Meiji 13). In order to cultivate good timber such as Japanese cypress and Japanese Spanish mackerel throughout the country, the seeds of trees collected in well-known good timber-producing regions were transferred to government forests and government-owned forests in various regions for sowing.

However, no matter how many "famous seedlings" were collected from all over Japan and sown in other regions, in many cases they failed because they were not suited to local conditions such as climate. After such trial and error, the Meiji government established Obayashi and Kobayashi district offices throughout the country in 1886 (Meiji 19), and took the helm in developing a forestry policy tailored to local conditions.

According to a recent survey conducted by the Tokugawa Forestry History Institute on the holdings of forest management bureaus (organizations that took over the operations of the Dairin District Office, etc.), several management bureaus have preserved old documents and other materials related to forestry administration in the Edo period, which were used as reference materials in the formulation of forestation plans after the Meiji period. In other words, the bottom-up, community-driven forestry policy of the Edo period has been carried on since the Meiji period.

Although "Edo Gaku of Forests" is a history book, it touches on the state of forests in modern Japan. It is brief, but therefore the main points are easy to understand. The outline is as follows.

Immediately after the defeat in World War II, Japan's forests were in a state of extreme devastation due to overcutting during the war and postwar reconstruction efforts. Demand for lumber continued to increase throughout the 1950s, and the Forestry Agency received calls from various quarters for increased lumber production through aggressive logging of state-owned forests. At the time, Japan was severely short of capital, and importing foreign timber was not an option.

Against the backdrop of such public pressure, the "National Forest Productivity Enhancement Plan" formulated in 1957 called for the promotion of comprehensive development of undeveloped forests in the backcountry and the expansion of artificial forestation. The newly established Forest Development Corporation actively developed forest roads to secure transportation routes into the backcountry, and promoted the "conversion" of slow-growing broad-leaved natural forests to fast-growing coniferous planted forests. The goal of this "expanded afforestation" policy was to increase the number of planted forests and double the productivity of forests 40 years after the plan was implemented (1997).

The policy of expanded afforestation was extended to privately owned forests owned by prefectural governments and private landowners through administrative guidance and subsidies. Under the guise of responding to the increased demand for timber resulting from rapid economic growth, natural forests were cut down in large numbers, both in satoyama and backcountry areas, and replaced with coniferous trees such as Japanese cedar, cypress, and Japanese larch. The forestry industry boomed in the first half of the 1950s, but it did not last long.

In 1964, imports of foreign lumber were fully liberalized, and in 1969, the supply of price-dominant foreign lumber surpassed that of domestic lumber. In 1973, with the introduction of a floating exchange rate system, the yen began to appreciate, further increasing the price advantage of foreign lumber. In addition, the oil shock of the same year caused a contraction in domestic demand for lumber.

Domestic forest products were now in a situation where, if they were to compete in price with foreign timber, the more they cut down and sold, the more they lost money. As the area of planted forests increased at a rapid pace due to expanded afforestation, management costs also remained high. The special account for the national forestry business, which had boasted a surplus in the 1950s, turned into a deficit, and in 1998 the accumulated debt reached just under 4 trillion yen, making it impossible to repay the debt through management efforts alone.

The 1999 overhaul of the national forest business was a response to this situation, and while a scheme for debt repayment was created through transfers from the general account, the main functions of national forests were positioned as water and soil conservation and coexistence with humans. As for timber production forests, the ratio of timber production forests in the total national forests was reduced from 541 TP3T to 4% at one stroke. In other words, the policy emphasizing timber production that had been in place since 1957 was completely replaced 42 years later by a policy emphasizing the forest environment.

The book "Edo Gaku of Forestry," which was introduced in a rush, is a book that leaves a dense reading experience. This is because the reader is not merely acquainted with the state of forestry in the Edo period, but is also informed by an awareness of the problems of how to think about the present day based on this knowledge.

At the end of the overview chapter, there is a sentence that reads, "Our position today may approximate the situation as it was just at the beginning of the 18th century. I completely agree.

At the beginning of the 18th century, "80% of Japan's forests were bare due to overcutting in the 17th century" (Kumazawa Banzan). With this in mind, trial-and-error efforts to curb the use of forests and plant trees were continued in each region, and technology was shared through forestry books written by local government officials, which led to the restoration of a green archipelago over the next 100 years. The time to start solving the problems of the Edo forestry industry was "just at the beginning of the 18th century.

The forests of modern Japan have been over-planted with coniferous trees, and the pollinosis is terrible. Although the problems appear to be opposite in appearance - too much logging in the 18th century and too much planting in the 21st century - the structure is the same in the sense that we are trying to optimize a situation in which too much alteration of nature for human convenience is causing adverse effects.

It is no different in 2025 than it was at the beginning of the 18th century, when many people are trying to break through the current state of Japan's forests, and are trying to do so through a process of trial and error. At the risk of sounding self-serving, the Platinum Forest Industry Initiative is one such example. The changes for the next 100 years are just beginning. (Kotaro Nagasawa, Director, Platinum Initiative Network)

■Related Sites

Rediscovering the History of Tokugawa: Edo Studies in Forestry (Tokyo Do Publishing Co., Ltd.)