Updated by "Forest Circular Economy" Editorial Board on July 15, 2025, 6:03 PM JST

Editorial Board, Forest Circular Economy

Forestcircularity-editor

We aim to realize "Vision 2050: Japan Shines, Forest Circular Economy" promoted by the Platinum Forest Industry Initiative. We will disseminate ideas and initiatives to promote biomass chemistry, realize woody and lumbery communities, and encourage innovation in the forestry industry in order to fully utilize forest resources to decarbonize the economy, strengthen economic security, and create local communities.

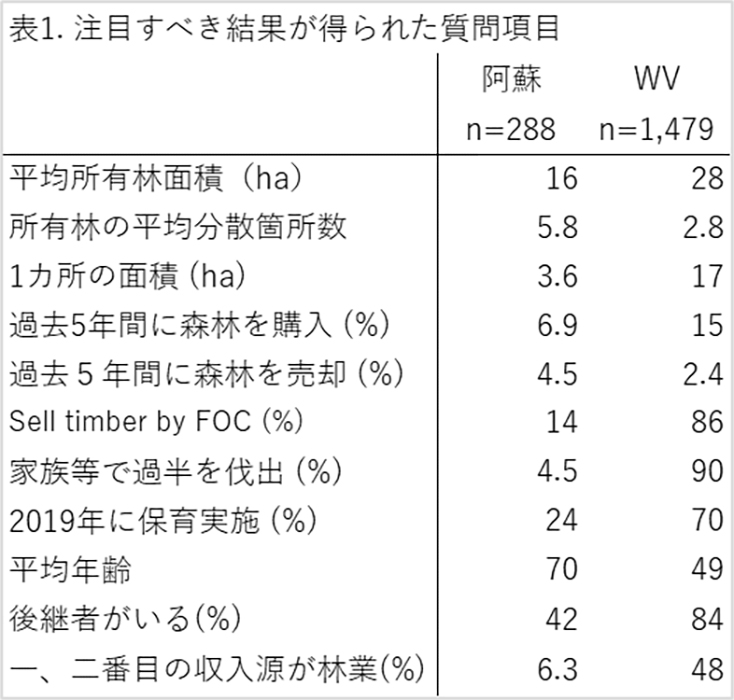

The Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute of the National Forestry Research and Development Institute (FFPRI) has clarified how privately owned forests are linked to forestry income by comparing regions in Japan and Austria, which share some similarities with Japan in terms of social systems and forest environments. The two organizations surveyed were the Aso Forestry Cooperative in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan, and the Federation of Forestry Cooperative Associations (WV) in the Austrian state of Styria. Questionnaires to members and field surveys revealed clear differences in the scale of management and income structure of forestry households in the two countries.

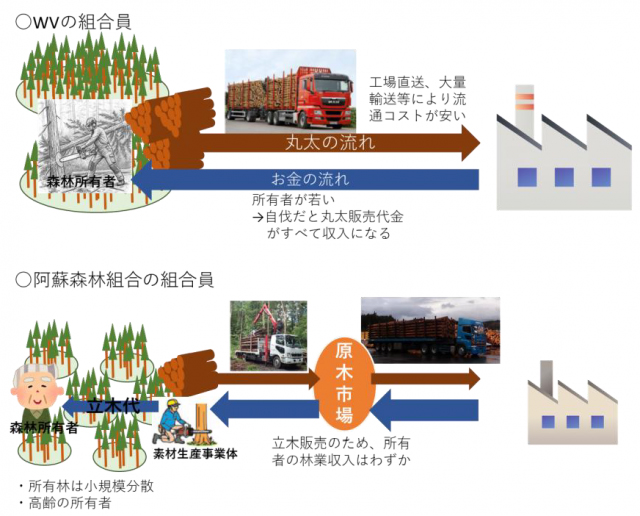

Both the Aso Forest Association and the WV are located in the mid-mountainous area, and share the same characteristics in that they both have many small- and medium-sized private forests, and that they are engaged in combined agroforestry management. The survey showed that the forests owned by each member of the WV were larger than those owned by the Aso Forest Association, both in terms of area per location and total area. This confirmed the reality that forestry families themselves secure stable forestry income through "self-logging forestry," in which they harvest and carry out logging themselves.

So why is it that large forest holdings are maintained and active forestry management is possible in Austria? The study points to the importance of the social systems behind this, particularly the inheritance system and legal regulations.

One is the existence of an agroforestry pension system. In Austria, it is necessary to transfer agricultural and forestry land to one's successor in order to receive an agricultural and forestry pension. This system removes the incentive to continue to own land even at an advanced age, and encourages early generational change, or inheritance before one's death. This will enable the younger generation, who are motivated and strong, to become involved in forestry as responsible managers at an early stage.

In addition, there is a functioning mechanism to prevent fragmentation of forests. In Austria, the custom of "one-child inheritance" has traditionally taken root, and in addition to this, laws and regulations such as the Land Transaction Law and the Forest Law restrict the easy division and conversion of land. These institutional and customary backgrounds provide the basis for maintaining and securing the scale of forest management that has been handed down from generation to generation and for continuing profitable forestry operations.

One of the reasons for the high profitability is the low log distribution cost. In Austria, the owner's forests are large, and self-managed logging is common, making it easy for the owner to take charge of the logging, removal, and shipping processes. This structure leads to simplification and efficiency in the distribution process, which in turn contributes to cost reduction.

In contrast, the Aso Forestry Association is facing a lack of successors and the dispersal of owned forests, resulting in little forestry by self-logging, making it increasingly difficult to continue management. In fact, many owners are leaving the forestry business due to the challenge of securing successors. In Japan, the fragmentation of forest land, inadequate distribution infrastructure, and lack of institutional support have combined to make it difficult for forestry to become a stable livelihood.

Through the case of Austria, which has much in common with Japan in terms of social structure and forest conditions, this study has shed light on the institutional and economic conditions necessary for sustainable forest management. Promoting the revitalization of privately owned forests by securing appropriate forest inheritance and ownership, improving the efficiency of forest distribution, and improving the legal system will be the key to revitalizing community-led forestry in Japan as well.

*Terminology

<Hayashiya>

This is a generic term for households that own forestland and does not include corporations such as companies.

<Self logging

A forest owner harvests standing timber from his or her forest by his or her own or his or her family's own labor, without outsourcing to a contractor, and processes the timber into logs for sale.