Noto's Satoyama and Satoumi, supported by forestry, is also working to revive the area by making use of its forestry heritage and Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System

Updated by Yuho Hitomi on September 03, 2025, 9:32 PM JST

winning hand containing one of each terminal and honor tile plus one extra copy of any of them

Yuho HIFUMI

Ishikawa prefecture (Hokuriku area)

He joined the Ishikawa Prefectural Government in 2012. After working on forest planning and forest GIS, he worked as a forestry extension advisor at the Agriculture and Forestry General Office, where he was involved in the registration of "Noto's Ate Forestry" as a forestry heritage site and the establishment of the "Creative Reconstruction Platform for Noto Using Ate Forestry and Noto Hiba" after the Noto Peninsula Earthquake of 2024. He holds a Master's degree in Global Environmental Studies from Kyoto University. He is a Noto Satoyama Satoumi Meister at Kanazawa University. Forest General Supervisor (Forester).

The Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture experienced a combination of disasters unprecedented in the history of the prefecture: the Noto Peninsula earthquake on January 1, 2024, and the Okunoto torrential rainfall in September. In the affected areas, housing reconstruction and infrastructure restoration are gradually progressing, and people are beginning to rebuild their lives and livelihoods. Noto, which has inherited traditions and wisdom to make the best use of nature's blessings in daily life, was recognized as a World Agricultural Heritage Site (GIAHS) by the FAO in 2011 and was globally recognized as a model of sustainable agriculture, forestry, and fisheries system "SATOYAMA SATOUMI," but the earthquake and tsunami destroyed many houses and caused the uplifted However, the earthquake and tsunami destroyed many homes, and the rising coastline and landslides have drastically changed the landscape of the satoyama built by our ancestors. This section looks back at the forests, forestry, and lumber industries that supported the rich civilization of the peninsula in the past.

The Noto Peninsula, with its low elevation and few steep mountains, has been settled by humans since the Jomon period, and the mountains have long been easily accessible to people. Few primary forests remain in Noto. The valleys and lower to middle slopes are planted with artificial forests such as cedar (most of which were planted during the postwar period of afforestation expansion), and secondary forests of red pine and konara oak extend from the upper areas to the ridges. The landscape of secondary forests has been maintained by the people who made charcoal and salt in the area, and what we see today are young trees that have grown into large trees.

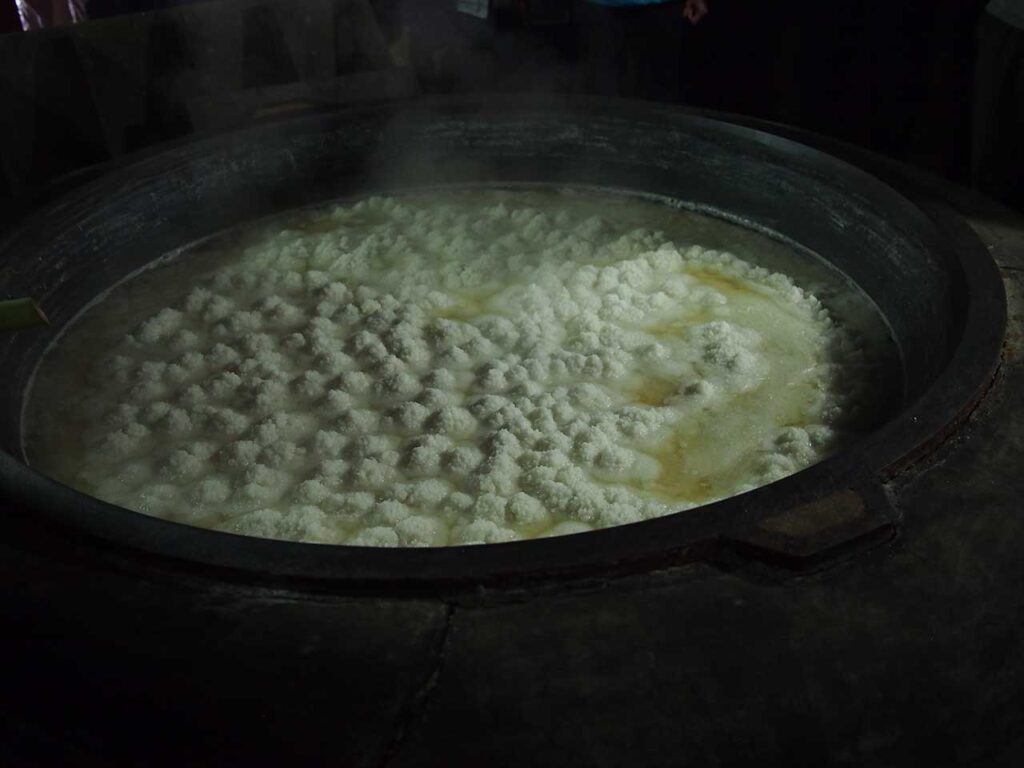

In Noto, salt has been produced for about 400 years using the Agehama method, in which seawater is sprinkled on the beach and then boiled in a cauldron, and is one of the components of the "Noto Satoyama Sea" World Agricultural Heritage site. Until the beginning of the Showa period, the Noto Peninsula had many salt farm communities along the coast. During the feudal era, people engaged in salt production were called "hamashi," or "salt farmers," and they obtained fuel (salt wood) for boiling seawater by purchasing the right to use mountains with "salt rice" loaned by the Kaga Clan. At its peak in the early Meiji period, it is said that 400,000 bales (approximately 20,000 tons) of salt were produced annually and sold nationwide. Since approximately 2 tons of saltwood was required for each ton of salt produced, a simple calculation indicates that 40,000 tons of firewood were consumed annually.

This is not much different from the total amount of wood chips used for papermaking and biomass power generation in Ishikawa Prefecture's current wood production, and is expected to increase further if other forest products such as charcoal are added to this total. In pre-modern Japan, forests were an important source of energy, and wood and coal forests were found throughout the country, and Noto was no exception.

In May 2023, Noto's forestry was registered as Ishikawa Prefecture's first "forestry heritage" by the Forestry Society of Japan. Forestry Heritage is a system for registering land, facilities, and technologies that illustrate the history of forestry development in various regions of Japan as "heritage" that should be preserved for future generations. Noto's ate forestry also has characteristics not found in other forestry regions.

Ate is the name given in the Noto region to the Japanese cypress asunaro (scientific name: Thujopsis dolabrata var. Hondae), a coniferous tree in the Asunaro genus of the cypress family, and is the same species as Aomori's hiba (hiba). Incidentally, it has nothing to do with the so-called "guess timber," which refers to the bent part of the timber. Of the approximately 140,000 hectares of forest area in Noto, 72,000 hectares, or about half, is planted in planted forests, of which the second most commonly planted species, after cedar, is atte.

In addition to reproducing sexually by seed, Hinoki asunaro also reproduces clonally, rooting from branches to increase its population. The young clonal trees survive in the dark forest by taking advantage of their high shade tolerance and wait for the opportunity to grow. Taking advantage of these characteristics, various methods have been used to establish Ate forests, including fusejo (*1), cuttings, and "aerial cutting" (*2). Ate is often mixed with cedar, or planted under cedar or ate overstory trees to create mixed forests, two-tiered forests, three-tiered forests, and various other types of forests. It is characterized by its flat, glossy, scale-like leaves, which give it its scientific name "dolabrata" (like an axe), and are a key to distinguishing this species from cedar.

Because the leaves of the atte are thicker than those of the cedar and cypress, which allow less light to penetrate, the ground surface is dark inside the atte forest, giving it the atmosphere of some ancient forest.

Hinoki asunaro lumber is stronger than cedar and more resistant to moisture and termite attack, and has long been favored in Hokuriku as a building and civil engineering material. Although the Noto Peninsula originally had natural forests of ates, there was not enough to use as a resource, and until the middle of the Edo period (1603-1867), large quantities of hiba timber from the Tohoku region were transported to the region by Kitamae-bune ships for use. However, documents written from the latter half of the Edo period to the Taisho period (1912-1926) describe the large shipments of ates processed into square timbers and boards from the port of Noto to Kanazawa and Toyama, indicating that the resource of ates was enhanced during this period. People living in the mountainous areas of Noto, where there is little flat land, probably took time out from their busy farming season to diligently plant ake in an effort to become as economically prosperous as possible.

It is also designated as the base material for the traditional craft "Wajima-nuri" and is used as a material for kiriko (*3), a symbol of Noto's festivals. As a timber, Ate supports the development of Noto's satoyama and satoumi, and is closely connected with the local culture. Ishikawa Prefecture designated the Ate (Hinoki asunaro) as a "prefectural tree" in 1966.

Against this background, the forestry heritage "Noto's Ate Forestry" covers the "planted forests" of Ate that span three cities and two towns in the Noto region (Wajima City, Anamizu Town, Nanao City, Noto Town, and Suzu City). It also consists of technical and historical elements related to forestry, such as "technical systems" related to sapling production and forest cultivation, and the "original ates," natural treasures that are said to have been brought from the Tohoku region during the Tensho era (1615-1868). In the process of afforestation, several different species were found to grow at different rates and of different materials, and each species has been used for different purposes, such as construction and crafts. This is an element unique to the Ate forestry industry and not found in Aomori hiba (Aomori hiba), which is primarily a natural forest.

The fact that a forest created by human hands is recognized as a heritage site is an event unique to Noto, which has a history of nurturing a rich biota and culture while maintaining a mutual relationship between nature and people.

In the Noto Peninsula, semi-natural landscapes maintained by agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, as exemplified by the Shiromai Senmaida, and traditional ritual events such as village festivals and "ae-no-koto" have been handed down to this day through local efforts. The United Nations University and UNESCO advocate the concept of "biocultural diversity," which states that in areas rich in biodiversity, cultural diversity is also protected at the same time, and have pointed out that Noto is a hotspot of biocultural diversity (an important area for conservation). For example, in addition to poison ivy, Wajima-nuri lacquerware is made from several species of trees, such as atate, zelkova, and hohonoki, and many other forest-derived materials are used for the base, such as spatulas for lacquering, charcoal for polishing, and wild plants for designs in maki-e and chinkin lacquerware.

The population of Noto has been declining almost continuously since the end of World War II, and the region has been suffering from a lack of local leaders. The GIAHS has a proven track record of reexamining local resources from a global perspective and linking them to branding of agricultural, forestry, and fishery products, tourism, the creation of educational opportunities, and measures to promote immigration.

The registration of forestry heritage is another mechanism to rediscover diverse forestry practices and to certify the value of forests to local culture. We hope that Noto's ate will connect with various players involved in forests and trees, and create ripple effects such as Noto's recovery, revitalization of the forestry industry, and preservation and transmission of traditional culture. (Yuho Hitomi, Forest Management Division, Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Ishikawa Prefecture)

*1...Renewal technology in which plant branches and leaves are pressed against the ground to fix them in place and promote rooting from the ground.

2...This method is said to have been proposed by Mr. Tetsuo Ishishita, an arthropathic forestry expert in Wajima City. Even today, most of the atte saplings sold by forestry cooperatives are produced using this method.

*3...Giant Hoto lanterns (faceted lanterns) that lead the portable shrines at festivals

■References

Shigemitsu Shibasaki and Kazunari Yamaki (eds.), Forestry Heritage.

■Related Sites

Ate Forestry of Noto General Inc.

World Agricultural Heritage "Satoyama Sea of Noto" Information Portal