Why did non-native conifers take root in Inokashira Park? How to enjoy forests living in the city

Updated by Kazuo Watanabe on October 07, 2025, 9:21 AM JST

Kazuo WATANABE

As a forest instructor, he spreads knowledge about trees and explains the natural environment, and teaches at NHK Culture Center, Mainichi Culture Center, Yomiuri Culture, NHK Gakuen, and others. He is the author of "Trees in Parks and Shrines," "15 Mysteries to Enjoy Roadside Trees," "Why Do Hydrangeas Collect Aluminum Poison in Their Leaves? Completed the graduate course at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Doctor of Agriculture.

Some people may make it a routine to take a stroll in a park for their health or to refresh their spirits. Parks vary in size, facilities, and history. This time, we would like to introduce Inokashira Park in Tokyo as one such park with a long history. Inokashira Park (officially Inokashira Onshi Koen) is a metropolitan park straddling Mitaka City and Musashino City in Tokyo. Although it is best known as a cherry blossom viewing spot, many people stroll around Inokashira Pond, the center of the park, regardless of the season. Inokashira Pond is located at the headwaters of the valley that carves the Musashino Plateau, and was formed by underground water that gushed out from the plateau. In the Edo period (1603-1867), it served as a source of water for the Kanda water supply, helping the people of Edo. Although the pond is no longer used as a water source, it provides visitors to the park with a spacious waterside view.

Inokashira Park is close to JR Kichijoji Station, but a walk along the Kanda Waterway from Inokashira Koen Station on the Keio Inokashira Line provides a quiet and atmospheric stroll. Around the Hyotan Bridge, where the water from Inokashira Pond flows out into Kanda Josui, there are several coniferous trees with straight trunks. Some of them have what look like stakes rising up from their roots (Photo 1). It is a strange sight to see stumpy stakes sticking out of the ground. These pile-like structures are called breathing roots (aerial roots), and they are said to play a role in breathing by rising into the air in place of the original roots, which have become difficult to breathe after being immersed in water. It is like a snorkel that a diver puts out on the surface of the water. It may look as if it will eventually grow and produce branches and leaves, but it never grows and produces branches and leaves. It is only a root.

The tree that produces these unusual roots is a coniferous tree from North America called rakuso (ochiba pine). The rakusyo prefers waterside locations and is also known as "swamp cedar" because it grows in marshes and swamps. When written in Chinese characters, rakusyo is "ochiba-matsu" (fallen feather pine). The name comes from its deciduous nature (ochu), its leaves that resemble bird feathers (hane), and the fact that it is a coniferous tree (matsu). Its trunk grows straight and tall, giving the tree a beautiful shape.

It was around 1930 that rakusyo trees were planted along the shores of Inokashira Pond. The rakusyo, which is native to North America, was a novel conifer brought to Japan during the Meiji period (1868-1912), and was acquired from the Forestry Experiment Station in Meguro, Tokyo. It was probably planted around Inokashira Pond, taking into consideration the fact that the land with a lot of water is suitable for its growth.

The area around Inokashira Pond was established as a park in 1917. Today, the area around the pond is covered with cherry trees and other broad-leaved trees, but when the park opened, Inokashira Pond was surrounded by a dense cedar forest. The cedar forest was created in the Meiji era (1868-1912) to protect the water source. The walking path around the pond passed through a grove of cedar trees, creating a solemn atmosphere. On the other hand, in 1936, an aquarium was newly built in a part of the Nature and Culture Park (an area including a zoo) located in a part of Inokashira Pond (a branch park), and the rakusyo trees scattered along the pond were transplanted to that site. Perhaps the bright groves of foreign conifers, unlike the dark cedar forests, caught the attention of visitors to the park.

The cedar forest that spread along the pond before the war was cut down by the military at the end of the Pacific War, and no trees remain today. At the time, there was an extreme shortage of lumber, and the cedars that were cut down were used to make coffins for air raid victims and for air-raid shelters. After the war, zelkova trees, cherry trees, Japanese Spanish oak, yellow maple, and katsura were planted along the pond, replacing the cedars, and the area became a rather light deciduous broad-leaved forest. In particular, many cherry trees were planted, and the area became a popular cherry blossom viewing spot in spring, attracting many visitors. In addition to rakuso, metasequoia trees, which are "living fossils" and will be described later, were planted in a branch of the Nature and Culture Park on the west side of the pond, creating a grove of bright deciduous coniferous trees.

The metasequoia is a tree similar to the rakuso. The shape of its leaves, its deciduous nature, and its tree form are similar. However, unlike the rakuso, it does not have aerial roots like stakes at its base. And the metasequoia is a coniferous tree native to China. The metasequoia became known to the public relatively recently, about 80 years ago. Until then, the metasequoia was thought to be extinct from the earth. However, in 1946, living metasequoia trees were discovered in China. It was thought to be extinct, but it survived only in China, and at the time it was talked about as a "living fossil. That is why all metasequoia trees planted in Japan were planted after the war.

The Inokashira Nature Park branch of the Inokashira Nature Park currently exhibits aquatic life and birds. The rakuso and metasequoia trees planted around the park create a forest of trees. These trees are elegant even when viewed from their roots, but their beautiful shapes can be appreciated when viewed from the other side of the pond. Both trees are deciduous, which is unusual for coniferous trees, and their leaves turn brick red in the fall and early winter. The grove of metasequoia and rakuso trees with their autumn leaves visible over the pond is magnificent (Photo 2). Inokashira Park is not far from central Tokyo. Why not take a stroll around the pond while tree-watching with a camera and a tree book in hand? (Kazuo Watanabe, forest instructor)

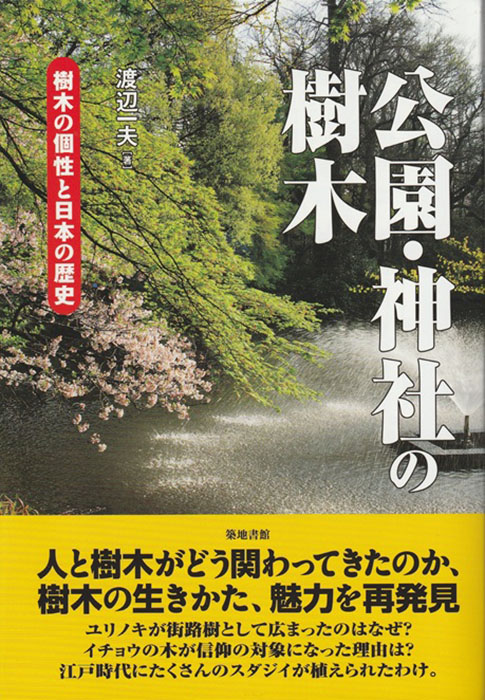

Trees in parks and shrines"

Written by Kazuo Watanabe, published by Tsukiji Shokan

An oasis of greenery loved by people, this book introduces the history and episodes hidden in this oasis of greenery. Through the trees in parks and shrines, this book will rediscover how people have been involved with trees, the way trees live, and their charms.

<Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Sleepless Platanus

Chapter 2: War-Torn Azaleas and Dogwoods

Chapter 3: Enoki, the History of Suigo

Chapter 4: Sudajii fought the Great Fire of Edo

Chapter 5 Camphor Tree from Taiwan

Chapter 6: Why did Eiichi Shibusawa build the park?

Chapter 7: How Ginkgo Came to Be Worshipped

Chapter 8: 5,000 Years of History Hidden in the Cherry Hill