This book explores the life course of a forestry technical official who dedicated himself to the modernization of Japanese forestry, and how it This book explores the life course of a forestry technical official dedicated himself to the modernization of Japanese forestry, and how it intersects with the history of slowly growing cedar plantations.

Updated by Nobuyuki Yamamoto on November 04, 2025, 8:45 PM JST

Nobuyuki YAMAMOTO

Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, National Forestry Research and Development Institute

Director of Forestry Management and Policy Research Area, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, National Institute of Forestry Research and Development / Specializes in forest policy and forestry economics. His recent research focuses on modernization and forests and forestry. His publications include "Forests and Time: A Social History of Forests", "Long-Term Sustainability of Local Forest Management: Future Perspectives from 100 Years in Europe and Japan", and "Theory of Forest Management Systems". His research on the modernization process of forest management systems won the Prize for Academic Achievement from the Forestry Economics Society of Japan, and "The Origins of the Forest Planning System in Japan" won the Paper Award from the Forestry Society of Japan.

In my edited book, "Forests and Time: A Social History of Forests in Local Communities," I adopted the concept of life course analysis as the theoretical framework that runs through the entire book. Life course analysis was proposed by the American sociology of the family, which adopted the results of developmental psychology, and the concept has been adopted and developed in various academic fields, including historical sociology. Its characteristics are that it places a person's life in the context of history and emphasizes socioeconomic influences.

Life course analysis assumes that a certain age group of generations that have encountered major social events and been branded by history can be grasped as a group that shares the same social experiences and has the same social reality. By doing so, "a way is opened to reveal social and historical changes by arranging a wide variety of unhelpfully diverse materials" (Kiyomi Morioka, "Kikketsu Sedai to Ibisho" [The Decisive Generation and the Testament], Shinchi Shobo, 1991, p.225). In this paper, we will try to decipher one aspect of forestry modernization in Japan from the perspective of life course analysis.

One of the characteristics of Japan's modern forest management system is that the national forestry technical bureaucracy has consistently played a major role from the prewar to the postwar period.

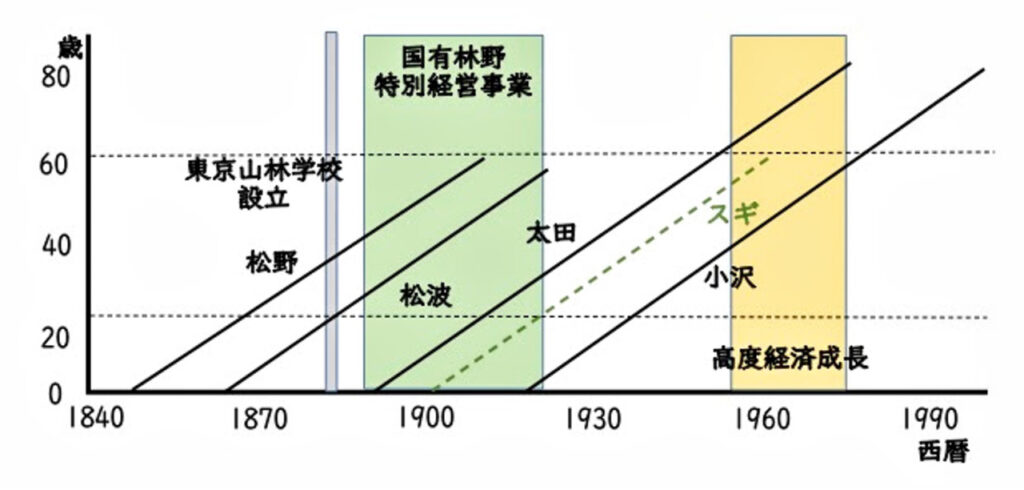

The figure depicts the lives of four forest engineering officials. The horizontal axis of the figure represents historical time from 1840 to 2000, and the vertical axis represents the age of each person. Thus, the four shaded lines on the figure indicate how old each person was in a given year. The shading orthogonal to the horizontal axis represents three periods that had a major impact on forest management in Japan: the establishment of the Tokyo School of Forestry, the National Forestry Special Management Project, and Japan's rapid economic growth. In addition, the period of less than 40 years sandwiched between two dotted lines orthogonal to the vertical axis, drawn in the early 20s and at age 60, represents the period of his career as a forestry technology bureaucrat.

Let's start with the horizontal slice. In the leftmost diagonal, we see Matsuno Hazama (1847-1908), born in 1847 (Koka 4), who, after returning from his studies at the Eberswalde Higher Forestry School in Germany, was instrumental in establishing the Tokyo School of Forestry and the Forestry Experiment Station of the Forest Bureau in 1882 (Meiji 15). In the latter half of his life, he served in important positions as a forestry technical bureaucrat in the Forestry Bureau. He is one of the pioneers of modern forestry in Japan.

Matsunami Hidemi (1865-1922), indicated by the next shaded line, was born in 1865 (Keio 1), at the end of the Edo period. Matsunami graduated from the Tokyo School of Agriculture and Forestry as a third-generation student in the forestry department, and as a forestry technology bureaucrat, he played an important role in the early construction of Japan's forest administration. Tokyo Norin Gakko was the only institution of higher education in agriculture and forestry at the time, created by the merger of Tokyo Sanrin Gakko (Tokyo Forestry School) and Komaba Gakko (Komaba Agricultural School), both founded by Matsuno, and was the predecessor of the Faculty of Agriculture of Tokyo Imperial University. Matsunami long spearheaded the National Forestry Special Management Project, a major project in the prewar period, and put the management of national forestry on track.

The third shaded figure, Yujiro Ota (1890-1975), became a forest technology bureaucrat at the end of Matsunami's career. Ota, who studied forestry during the Taisho Democracy period and the development of Japanese forestry against the backdrop of the progress of Japanese capitalism, was one of the core members of the Korin-kai, the pioneering (predecessor) of the Japan Forest Technology Association, and devoted himself to improving the social status of forest technicians. As the head of the technical bureaucracy of the Forestry Bureau, Ota lived through the forest administration that was being swallowed up by the wartime regime, and was forced to make frequent and painful decisions. After the war, he taught at Shinshu University, Nihon University, and other universities, and worked to foster the development of future generations.

And the rightmost shaded line is Ozawa Imachoyo (1918-1999). Ozawa was appointed to the Imperial Forestry Bureau in 1944, in the shadow of the war's end. At the Forestry Agency after the unification of the forestry administration, he worked hard on the National Forest Productivity Enhancement Plan, an important policy during the period of expanded afforestation, and was in charge of forest administration during the period of extraordinary increase in demand for timber during the period of rapid economic growth. Unfortunately, he retired from the Forestry Agency due to an injury sustained during his tenure, but he spent the rest of his life as an academic, writing voluminous academic works such as "A History of Forest Management in Germany.

On the other hand, what about the vertical cut-off? For example, if we look along the dotted line in the early 20s, we can see what socioeconomic events each of them encountered in the early stages of their careers as forest technology bureaucrats. Matsuno and Matsunami were born in the early stages of the modernization and development of forest administration, respectively; Ota in the late Taisho period, when the prewar forest administration was maturing; and Ozawa in the period of rapid economic growth. Despite their personal differences, they encountered the same historical events at the same age when they were expected to play a certain role in society.

The other dotted green line drawn parallel to the four lines represents the growth of a cedar planted in 1900. As a matter of course, trees, like people, grow year by year. Therefore, on the same diagram that shows the western calendar and the age of each individual tree, we can also superimpose the annual rings that represent the life course of the tree, so to speak. Especially in the case of planted forests, which are artificially created by planting a large number of trees, it is possible to clearly show the relationship with social time through this kind of graphical representation, similar to that of human generations.

Let us look in turn at the intersection of the dotted lines in the figure and the solid lines showing the life courses of the four forestry technology bureaucrats. Modern forestry, which Matsuno brought back to Japan in the early Meiji period, experienced growth. The artificial cedar forests planted during the National Forestry Special Management Project promoted by Matsunami in his prime reached 60 years of age during the period of expansion of afforestation that Ozawa initiated after the war and supported the demand for lumber during the period of rapid economic growth, after the turbulent period that Ota led from the prewar to the postwar period.

In the early postwar period of afforestation, Ozawa, who was born half a century after Matsunami, was in his prime, just as Matsunami was when the cedar trees were planted. As we enter the 2020s, the cedars planted by Ozawa are about to be harvested again. (Nobuyuki Yamamoto, Director of Forestry Management and Policy Research, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, National Institute of Forestry Research and Development)

Forests and Time."

Edited by Nobuyuki Yamamoto, published by Shinsensha

The life of a tree can span decades or centuries. A long-term time scale is essential for building a sustainable relationship between forests and local communities, but it is not something that can be carried out in the lifetime of a single person. With an eye on farming and mountain villages, where it is becoming increasingly difficult to pass on the forests to the next generation, we will explore the future of a better relationship between forests and people, using the history that people have carved into the local forests as a guidepost.

<Table of Contents

Introduction: Forest Time and Human Time Nobuyuki Yamamoto

Chapter 1: People Who Encountered Yamazukuri Shimazaki Yoji and the Forest School Atsuro Miki

Chapter 2: Inheritance of Mountain Village Society and Women's Life Course: Women's Progress in 200 Years of a Mountain Village in Tochigi Prefecture Miho Yamamoto

Chapter 3: Life History of a Village and Its Residents Living with Mountains and Rivers Taro Takemoto, Shuhei Sato, Sho Matsumura

Chapter 4: Modernity and Forests in Hamadori, Fukushima Prefecture, Chapter 4: Nobuyuki Yamamoto

Chapter 5: The Interconnection between the Pulp and Paper Industry and Local Sustainability

Chapter 6: The Era of the Akai School: The Origin of Domestic Timber Supply Development in a Local University Yoichiro Okuyama

Chapter 7: Party and Expertise in Forest Management Changes in Forest Policy and Local Practices in Tenryu and Fuji Minami-Foothills Kazuto Shiga

End of Chapter Nobuyuki Yamamoto, Continuing to Re-weave the Relationship between Forests and People