The surviving Japanese cedars of the Japanese archipelago point to future forest development

Updated by Kotaro Nagasawa on November 28, 2025, 8:51 AM JST

Kotaro NAGASAWA

(Platinum Initiative Network, Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1958. (Engaged in research on infrastructure and social security at Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. During his first few years with the company, he was involved in projects related to flood control, and was trained by many experts on river systems at the time to think about the national land on a 100- to 1,000-year scale. He is currently an advisor to Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. He is also an auditor of Jumonji Gakuen Educational Corporation and a part-time lecturer at Tokyo City University. Coauthor of "Introduction to Infrastructure," "New Strategies from the Common Domain," and "Forty Years After Retirement. D. in Engineering.

*Previous column is here.

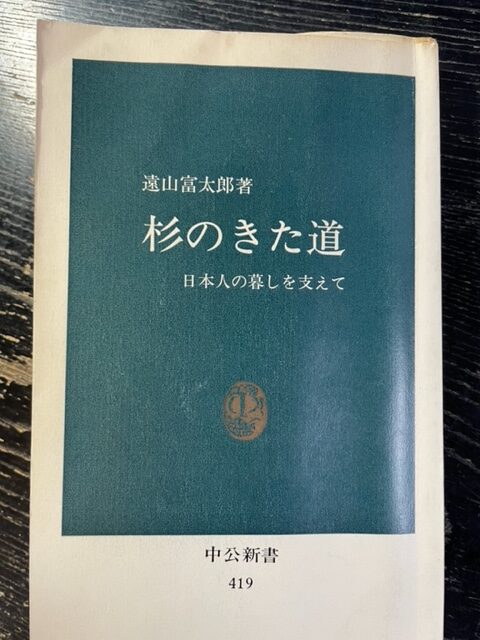

The "easy-to-break" Japanese Cedar Built Japan: Tomitaro Toyama's "The Road Cedar Took: Supporting the Lives of Japanese People" (Part 1)

The latter half of this book, as its title suggests, explores the theme of where the Japanese cedar—so deeply ingrained in Japanese life—originated. The outline is as follows.

The Japanese cedar also has its own history. During the warm Pliocene epoch (5.33 to 2.58 million years ago) in the Northern Hemisphere, a group of tree species known as the Metasequoia flora dominated. Among them were various genera of the Cupressaceae family, from which the Japanese cedar, connected to modern-day trees, emerged.Subsequently, during the Quaternary Pleistocene epoch (2.58 million to 11,700 years ago), the Earth underwent a cooling period, alternating between glacial periods (ice ages) and interglacial periods.

During the Ice Age, various genera of the cypress family gradually disappeared from each region, surviving only in the warm lands of the Pacific Rim.The author writes, "As the most cold-tolerant species within the family, the Japanese cedar could truly be said to have been born to survive Japan's glacial period. Though called a glacial period, Japan's was not as severe as Europe's, where the north was covered by glaciers." The Japanese cedar nearly vanished from the world, yet it remained in Japan. It seems the Japanese archipelago and the Japanese cedar were destined to be bound together.

Nevertheless, glacial and interglacial periods bring changes to plant habitats. According to this book, a group of forests known as cold-temperate forests, including species like cedar and beech, repeatedly migrated northward and expanded to higher elevations during interglacial periods, only to retreat during glacial periods. Such patterns are known through analyzing pollen from that era found in geological strata.

The last ice age ended approximately 10,000 years ago. The period from then until today is called the Holocene. It is a warm era.

The Holocene also has relatively warm and cold periods. From approximately 9,500 to 4,000 years ago, it was warmer than today, with beech and oak dominating the Japanese archipelago. From 4,000 to 1,500 years ago, it was relatively cold, and cedar became dominant.

In other words, 2,000 years ago, during the Yayoi period, the Japanese lived in an era dominated by cedar. Then ironworking technology arrived from the continent, making tree felling easier. Considering the inseparable relationship between the Japanese and cedar wood that followed (see Part 1), this was arguably a most fortunate encounter. One example of this is the Toro Ruins.

Incidentally, there seems to be debate over whether Japanese cedar consists of one or two species. The cedar commonly called "omote-sugi" (front cedar) grows on the Pacific side, with representative examples being Yoshino cedar (Nara Prefecture) and Yakusugi (Yakushima Island). "Ura-sugi" (back cedar) grows on the Sea of Japan side and includes Akita cedar and Kitayama cedar (Kyoto Prefecture). This book also touches upon this point.

Cedar trees are widely distributed in regions with annual precipitation of 2,000 mm or more. Specifically, this includes central Honshu (Kinki and Chubu regions), spanning both the Pacific and Sea of Japan coasts. This "distribution on both the Sea of Japan and Pacific coasts" is also a characteristic of cedar; for example, cypress trees are found almost exclusively on the Pacific coast.

Thus, whether the Japanese cedar trees on the Sea of Japan side and the Pacific side are the same or different has been the subject of comparative research from various perspectives, including leaf measurements. According to the author, no conclusion has been reached (though the book is 50 years old), but I find it an interesting topic.

This book is filled with descriptions that captivate the reader right up to the very end. For example, near the end, there is the following passage: Cedar is a unique plant.

When you think about it, the cedar tree is a strange plant. Its leaves, which seem simple enough to call needles, are remarkably diverse. They cling to the twigs as if flowing slowly, and the neighboring leaves cling in the same way, together encircling the twig. The twigs and branches merge while being wrapped by the leaves, becoming slightly thicker branches, and then the leaves cling again. It becomes impossible to distinguish between leaves and branches.

Both buds and roots grow with seemingly boundless adaptability. Among conifers, pine roots exhibit differentiation: once they reach a certain size, they become either short roots that cease growing and focus solely on nutrient absorption, or long roots that continue growing while branching off—essentially forming underground branches and leaves.(Omitted) Cedar and its relatives are different. They can freely extend or absorb nutrients at any root tip as needed. This plastic nature may be evidence of an undifferentiated, ancient form. Yet, according to current paleontological data, the emergence of cedar is a recent event. This too is strange."

The book concludes by noting that Katsura Imperial Villa is constructed entirely of cedar. Particularly noteworthy are the veranda floorboards, which feature a beautiful interplay of flat-sawn and quarter-sawn grain patterns. Furthermore, while Shōsōin is built of cypress, the treasure hall that has safeguarded the treasures of the Tenpyō era is constructed of cedar.

The world of cedar is profound. It serves as material for architecture and shipbuilding, as a source for daily necessities, preserves art treasures (Shōsōin), and even becomes an element of beauty itself (Katsura Imperial Villa). One might say that 2,000 years of Japanese history has been shaped alongside cedar.

And now, we are forging a new relationship with cedar. It involves creating timber-framed cities and utilizing it as a renewable energy source. If "The Path of Cedar" were to be written again a thousand years from now, the 21st century and beyond would likely be its main subject. (Kōtarō Nagasawa, Director, Platinum Concept Network)

*Note

This book was published in 1976, and some of the academic terminology and findings described herein reflect the state of knowledge at that time.

【About the Author】

Born in Kyoto City in 1910 (Meiji 43). Graduated from the Department of Forestry, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University in 1933. Worked at Kyoto University's Experimental Forest (Headquarters, Karafuto, Ashio) from 1934 to 1944.From 1944 to 1952, he worked at Kawanishi Aviation Timber. In 1952, he became an associate professor at Shimane Prefectural Agricultural College. In 1955, he became a professor there. In 1968, he became a professor at the Faculty of Agriculture, Shimane University. He retired in 1974 upon reaching mandatory retirement age. He passed away in 2002.

■Notice of Event Featuring Mr. Nagasawa

Forest Circular Economy Talk Live Vol.1 How Can Our Local Forests Be Revitalized? Learning from France's Forestry Approach: Right Tree for the Right Place Friday, December 12, 2025 | 8:00 PM - 9:30 PM | Online |