In the construction industry, where skilled labor is scarce and the trend toward less skilled workers is advancing, wood construction is becoming a realistic solution.

Updated by Sogo Kato on December 15, 2025, 7:30 PM JST

Sougo KATO

Leaf Rain Co.

After working for a financial institution researching companies in the high-tech field, he worked as a supervisor at a landscape construction site before setting up his own business. He is interested in the materials industry, renewable energy, and wood utilization, and in recent years he has been writing about the forestry industry. With his experience of working in the forests in the past, he aims to write articles that explore the connection between the realities of the field and the industrial structure.

The expansion of timber construction in Japan is driven by policy demands such as decarbonization and the utilization of domestic timber. However, at the site level, another crucial factor cannot be overlooked: timber's material properties make it "easy to handle and reduce construction workload." Compared to reinforced concrete (RC) or steel (S) construction, wood is lighter and easier to process, reducing reliance on skilled labor on-site. In Japan, where the workforce in key construction trades is aging, factory-produced and assembly-based construction systems leveraging these characteristics could support the sustainability of a construction industry facing a skills shortage. In other words, the shift to wood construction is becoming an important option not only for environmental adaptation but also for considering future construction systems.

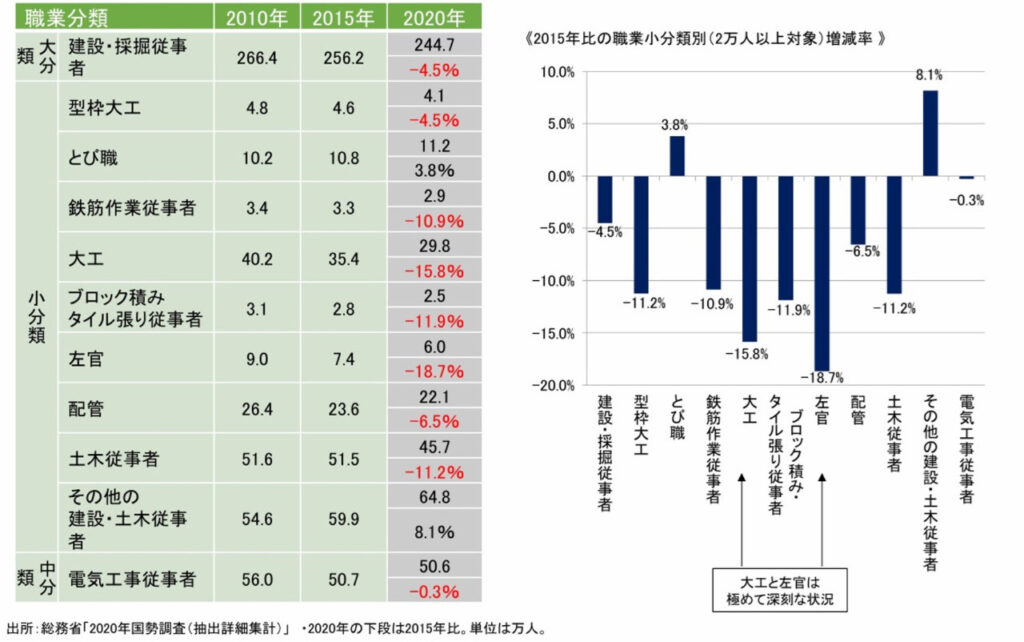

In the construction industry, the aging of key skilled trades such as carpenters, plasterers, and rebar workers is accelerating, with those aged 60 and over becoming particularly prominent, leading to a worsening shortage of workers. These trades require a long period of approximately 10 years to master, making it difficult for young people to stay in the field. Foreign workers also face language barriers, requiring even more time to become productive assets. While a certain number of young workers are present on construction sites, making the shortage less apparent, the disparity is significant between trades with a higher proportion of young workers (like wallpapering, drywall installation, and scaffolding) and those experiencing accelerated aging (like carpentry, plastering, and rebar work). The trades responsible for a building's structural framework face the most severe labor shortages.

Amid this accelerating shortage of workers, the traditional "on-site completion" construction model is showing signs of institutional fatigue. The shift toward less skilled labor—where processing and adjustments are moved to the factory, simplifying on-site work—is now unavoidable.

Furthermore, labor cost trends also confirm the shortage of workers. While the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism's labor rates continue to rise, these are merely the calculation standards for public works projects; the actual take-home pay received through the subcontracting structure falls below this figure. While carpenters, plasterers, and rebar workers all command nominally high rates, the actual take-home pay narrows the gap with ordinary laborers. This failure to provide compensation commensurate with the long apprenticeship period is considered a factor hindering the retention of younger workers.

Wood is lightweight and easy to handle, making it simple to cut, fasten, and adjust. This gives it high compatibility with factory production and unitization. These material properties support the shift toward reduced skill requirements and industrialization, offering a realistic solution for Japan, where a skills shortage is becoming structural. Overseas initiatives promoting wood-based construction also provide valuable insights for addressing similar structural challenges.

Against this backdrop, the shift toward wood construction is emerging not only as an environmental solution but also as a realistic option for ensuring the sustainability of the construction industry.

While the high skill dependency poses a challenge, industrialization leveraging wood's workability has achieved success overseas. According to Swedish Wood, the Swedish timber industry association, the combination of lightweight timber and prefabrication methods has become established. This construction system simultaneously enhances low-skill requirements and cost-effectiveness, achieving reductions in transportation costs by half, decreases in on-site personnel, and significant construction time reductions—such as completing buildings in 10 weeks that would take a year using conventional methods.

Meanwhile, in France, structural challenges inherent to timber construction have prevented the full realization of benefits seen in countries like Sweden. The lumber and primary processing sectors are fragmented among small-scale operators, investment in CLT and similar products has been slow, and the supply system is weak. Furthermore, regulations like fire standards drive up costs. According to data from the French Ministry of Agriculture and Food, in 19 projects in the Île-de-France region, the construction cost per square meter for timber structures was €1,972, approximately 11% higher than reinforced concrete structures. In other words, even with the same timber material, outcomes vary significantly depending on the industrial structure and regulatory environment.

In countries like Sweden where industrialization and supply systems are well-established, increasing the use of wood directly boosts productivity. However, the French example shows that without a corresponding industrial base and regulatory framework, the same results cannot be achieved. This offers important insights for Japan as it advances its own wood construction initiatives.

Wooden construction based on industrialization offers a practical alternative for Japan's construction sites, where skilled workers are aging, enabling productivity while reducing construction burdens. The ease of handling wood and its compatibility with factory processing hold significant meaning as we envision the next construction system, especially as the limitations of conventional methods become apparent.

However, for widespread adoption, stable timber supply, a sawmilling and processing system supporting industrialization, and the development of construction methods and certification systems tailored to Japan's unique regulations and market structure are indispensable. Both Sweden's success and France's slowdown demonstrate that whether these prerequisites are in place significantly influences the outcome. To sustainably expand timber construction, infrastructure development supporting both the construction industry and forest resources is essential. (Sogo Kato, Forestry Writer, Leafrain Inc.)