Belief in "native forests" and extensive reforestation practices both at home and abroad

Updated by Kotaro Nagasawa on January 23, 2026, 9:49 PM JST

Kotaro NAGASAWA

(Platinum Initiative Network, Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1958. (Engaged in research on infrastructure and social security at Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. During his first few years with the company, he was involved in projects related to flood control, and was trained by many experts on river systems at the time to think about the national land on a 100- to 1,000-year scale. He is currently an advisor to Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. He is also an auditor of Jumonji Gakuen Educational Corporation and a part-time lecturer at Tokyo City University. Coauthor of "Introduction to Infrastructure," "New Strategies from the Common Domain," and "Forty Years After Retirement. D. in Engineering.

*Previous column is here.

What Happens When Forests Are Left Untouched... The Perspective of "Potential Natural Vegetation" Reading Akira Miyawaki's "Plants and Humans: The Balance of the Biosphere" (Part 1)

In Plants and Humans, various communities in a single site undergo a transition from a pioneer plant community to a final community that is in balance with the climatic and soil conditions of the site and is interrelated with the external environment, including human activities. The transition toward the final community is called progressive succession. Potential natural vegetation is the final phase that the land would reach if all human intervention in nature were stopped.

There are very few plant communities (called primary vegetation) that have not been touched by humans. According to the authors' survey, the area of land in Japan that retains its original vegetation is a mere 0.61 TP3T. The ideal form of nature in the future can only be discussed based on the recognition of the current situation (called the current state of natural vegetation) once human intervention has taken place.

Latent natural vegetation is a third vegetation concept added to the original vegetation, which remains untouched by humans, and the existing vegetation, which has been altered by humans.

Potential natural vegetation is not always the same as the original vegetation. For example, if an evergreen broadleaf forest, such as a sudajii, is destroyed by human activities and the soil is drained away, it can no longer be restored, and the potential natural vegetation may be considered a red pine forest that can grow even on thin land.

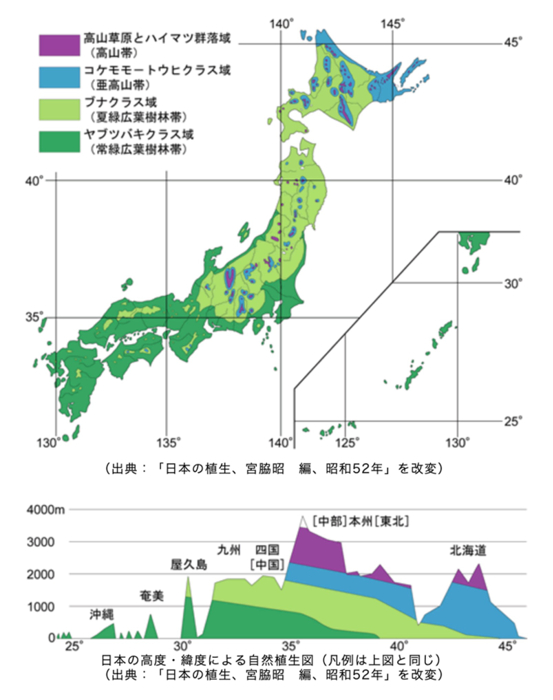

The concept of potential natural vegetation has spread around the world since the 1960s, and nationwide potential natural vegetation maps were created in the United States, the Soviet Union (at that time), and Eastern European countries. In Japan, Miyawaki and his colleagues surveyed the entire country and compiled the "Potential Natural Vegetation Map of Japan. It can only be described as a laborious work. The map shows a vivid contrast between the evergreen broadleaf forest areas from the three major metropolitan areas to the west of the Chugoku region and the summer green broadleaf forest areas from the mountainous areas of the Chubu region to the entire Tohoku region. In "Cedar Trails," it was written that cedar survived in Japan, but from the perspective of potential natural vegetation, coniferous forests, including cedar, have an extremely low presence.

How was this diagram created? One part of the methodology is described in "Plants and Man. In addition to botanical clues such as fragments of remnant natural vegetation, remnant natural trees, compensatory vegetation, mantles, and sod communities, individual vegetation is comprehensively determined from multiple measurements such as soil cross sections, industrial patterns, and land use patterns. Thus, it requires a skilled group of researchers and considerable expense and time." In reading his other works, the starting point is the creation of an existing vegetation map. After meticulously creating this map, land conditions and social conditions are evaluated and assessed, and future scenarios are drawn. It is true that this is a job that requires a craftsman's level of skill.

Based on this academic and practical accumulation, Mr. Miyawaki has worked to realize potential natural vegetation both in Japan and abroad. It is estimated that he has planted 40 million trees around the world. His activities were based on his belief that realizing vegetation rooted in the land is indispensable for creating disaster-resistant and vibrant communities. In his book, "The Power to See the Unseen" (Fujiwara Shoten, 2015), he wrote, "It is the real trees of the land that are strong against disasters. Genuine trees are those that can last for a long time without management."

I met Mr. Miyawaki only once before his death, about 20 years ago, when a young colleague and I visited his office in Yokohama, Japan, because we happened to be interested in his broadleaf tree-planting activities. I listened to his passionate thoughts with great interest. I think he was listening very seriously. Suddenly, Mr. Miyawaki, who had the appearance of an ancient samurai, looked me in the eye and said, "I am going to China next week to work on the plantation. I am going to China next week to plant trees. I'm going to China next week to plant trees.

For a moment, I felt elated. I thought about how I would answer. Petty thoughts like "what to do about the ongoing project," "how to explain to my family and company," "can I get an airline ticket," etc., came into my head and I tried to push back my elation. I don't know what I looked like. There were a few seconds of silence. Then Mr. Miyawaki gently removed his gaze and returned to his original story as if nothing had happened.

In another of Miyawaki's books, "The Acorn Forest That Protects Life" (Shueisha Shinsho, 2005), there is this passage: In 1960, upon his return from study in Germany, a German administrator asked him to visit Dr. Tsuyoshi Tamura of the Japan Wildlife Conservation Society. Dr. Tamura immediately said, "Thank you very much for coming. I am sure that our association will become more important than universities in the future. Mr. Miyawaki, please come and visit us tomorrow! He was puzzled by this enthusiastic invitation. He ended up helping the association on a part-time basis twice a week until it got off the ground. It is a passionate world.

This book is a combination of Miyawaki's strong personality and the atmosphere of the 1970s, and is filled with a special kind of heat. It is just so passionate. It also contains many thought-provoking statements that are still relevant today, 56 years after its publication, such as "Humans are only one member of nature" and "Plants are the main actors in the biological world. Humans may have some brains, but we must not be arrogant. Don't take nature lightly. Listen more to the voice of nature. That is the message I receive.

I would like to close with a quote from one of the sentences, which probably resonates with the Platinum Initiative Network.

If we carefully utilize the natural factors of our land, especially the green natural vegetation, based on the principle of coexistence with them, the limited nature of Japan's land will not only guarantee our healthy survival but also promise us a bright future as the foundation for the irreplaceable future development of the Japanese people." (p. 116 of this book)

(Kotaro Nagasawa, Director, Platinum Network)

*Note

This book was published in 1970, and some of the academic terms and findings in the text are expressions based on the state of research at that time.

【About the Author】

Ecologist, born in Okayama Prefecture in 1928. Graduated from the Department of Biology, Hiroshima University of Letters and Science. Doctor of Science. He has served as a researcher at the National Institute for Vegetation Research in Germany, professor at Yokohama National University, president of the International Society of Ecology, and director of the International Center for Ecology at the Research Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (RIEGES). His publications include "Nihon Vegetation Journal" in 10 volumes (Shibundo 1980-1996), "Green Environment and Vegetation Studies: Chinju no Mori wo Chikyu no Mori ni" (NTT Publishing 1997), "Inochi wo Mamoru Donguri no Mori" (Shueisha Shinsho 2005), "Plant a Tree! (Shinchosha 2006), "Chinju no Mori" (Shincho-Bunko 2007), "Chikara no Mono wo Mieru Chikara" (Fujiwara Shoten 2015), and many others. died in 2021.

Reference Links

NHK Books No. 109 Plants and Humans: The Balance of the Biological Society | NHK Publishing