Kumazawa Banzan, a pioneer of Japanese forest history, is an unbiased thinker.

Updated by Kotaro Nagasawa on July 16, 2025, 8:49 PM JST

Kotaro NAGASAWA

(Platinum Initiative Network, Inc.

Born in Tokyo in 1958. (Engaged in research on infrastructure and social security at Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. During his first few years with the company, he was involved in projects related to flood control, and was trained by many experts on river systems at the time to think about the national land on a 100- to 1,000-year scale. He is currently an advisor to Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. He is also an auditor of Jumonji Gakuen Educational Corporation and a part-time lecturer at Tokyo City University. Coauthor of "Introduction to Infrastructure," "New Strategies from the Common Domain," and "Forty Years After Retirement. D. in Engineering.

I have read three books in this column so far, trying to get an overview of the history of the Japanese people and forests. Among them, I have become somewhat curious about Kumazawa Banzan. Books dealing with the history of Japanese forests almost always mention him. To be honest, my knowledge of him is limited to "a Confucian scholar of the Edo period. Why does a 350-year-old Confucian scholar advocate forestation and why is his name always mentioned in the history of Japanese forests?

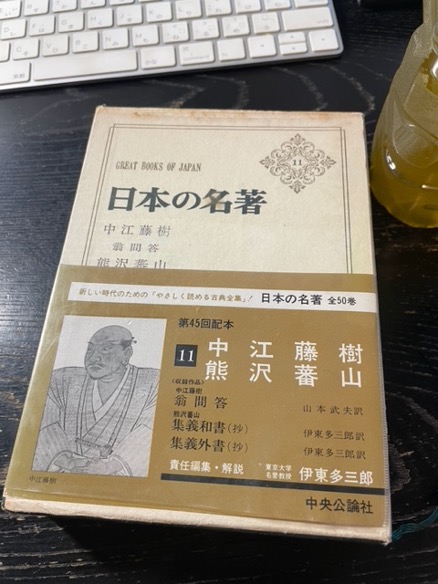

This time, I wanted to explore this area a little, so I read "Shugi Wa Sho" and "Shugi Gaisho," which are considered to be his main works. The old text was too demanding, so I looked for a text translated into modern Japanese (Chuokoron-sha, "Nihon no Meisho 11: Nakae Fujiki/Kumazawa Bansan," 1976). Used books are available on Amazon.

I would like to state in advance my impression after reading this book that Kumazawa Bazan's thoughts and writings have a strong appeal that can withstand the winds and snow of several hundred years. I would not be at all surprised if they are still being read 100 or 500 years from now. I hope to be able to convey even a small part of this in the following short article.

After spending a poor childhood in Kyoto as the eldest son of a poor ronin in 1619, just after the establishment of the Edo shogunate, Kumazawa Bazan was sent to serve in the Bizen Okayama domain at the age of 16 through the arrangement of a relative who could not bear to see him go, but for some reason he resigned four years later and moved to Omi. While staying with his mother's family, he studied at Nakae Fujiki's private school for about six months. He lived in extreme poverty here, and again at the age of 26, through the advice of a relative, he went to work for the Okayama Clan. He became famous throughout the country at the age of 35 for his brilliant handling of a major flood and famine in the Okayama domain. However, he was shunned by his chief vassals and resigned again at the age of 37. He moved to Kyoto, mingled with court nobles and Buddhist monks, studied Japanese classics, and began to publish his works. However, he was also suspected by the Kyoto governor, and was banished from Kyoto at the age of 48. Thereafter, he moved from place to place in Hyogo and Nara.

Some high-ranking officials of the shogunate sympathized with Bazan's views, and in response, he submitted a letter of opinion to the shogunate administration at the age of 66. However, the content of the letter was called into question and he was ordered to stay at his estate in Koga, Ibaraki Prefecture, where he died a guest death. He died there at the age of 73.

In describing his life, Issaku Suzuki (author of "Kumazawa Bansan to Goto Shimpei") writes that he was a "ronin Ryuten. Although he worked for the Okayama clan for a total of 15 years, he was basically an intellectual in the field. He was 54 years old when he published "Shugi Wa Sho" and 61 years old when he published its sequel, "Shugi Gaisho".

These were books of thought for the general reader of the time. They are written in a question-and-answer format. A friend or guest asks some question, and the author, Banzan, answers it, making them very easy to read. There must have been hundreds of questions and answers. The dialogue format is not unusual in this world, and is probably a standard form of writing.

The content of the dialogue is wide-ranging. The dialogue covered the state of moral character, the form of the reigning dynasty, tips for recruiting human resources, the attitude of lords, the importance of learning, views on life and death, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Christianity, as well as measures against samurai obesity, how to deal with colleagues and relatives with whom one does not agree, how to raise children, how to deal with insomnia, the national character of China and India, ideal tax revenue levels, the difference between thrift and stinginess, He also discussed the pros and cons of consanguineous marriages, the benefits of music, evaluation of historical figures, fostering local industry, educational policy, the need for secrecy (spying), and flood control. Bansan did his best to answer all kinds of questions, and it was very interesting without being boring.

For example, if someone says, "I do not have enough knowledge, so I will study," I would say, "Study is not for acquiring knowledge, but for improving moral character. A person who is knowledgeable but not virtuous is a bewitched one, and a person who is unwise but close to virtue is superior," he would caution. To the question, "Which is heavier, the lord or the parent?" he replies, "It depends on the time and the occasion. A sovereign does not say which is heavier, the lord or the parent. Even if the parent becomes a captive of the enemy, the righteousness of the sovereign and vassal must not be changed. However, if a parent suffers an unforeseen calamity, he or she must help the parent even if it means giving up his or her position and stipend, otherwise it cannot be called benevolence. When asked about his sexuality, he replied, "It is not something I am permitted to do. It is something to be done with patience. Each of his answers is full of flavor.

It is a book that is difficult to summarize, but if I were to forcefully summarize it, I would say that it is a good book of thought that presents a struggle between idealism and pragmatism, and then expresses a judgment based on what he thinks is the right way to go about it. I think this is a high-quality book of thought.

Although Banzan answers the questions of the common people warmly and courteously, he has a strong spirit of criticism toward society. He was particularly harsh on religion. India was a lowly country in the tropics, where people were ignorant of righteousness and humanity, and created the fiction of reincarnation to deceive people. The doctrines created by the disciples of the Buddha were nothing but lies. Prince Shotoku was guilty of importing them. In Confucianism, too, Zhu Zi studies, which is devoted to interpreting texts, and Yang Ming studies, which emphasizes one's own mind, are out of line with the attitude of Confucius, who learned how to be a sovereign from the three emperors and five kings of ancient times. If one is deceived by Christianity, the West will take over the country, etc.

If Banzan was such an unreserved and harsh critic of Japanese Buddhism, which had a history of 1,000 years at the time, and of Shuzi-gaku, which was adopted by the Tokugawa Shogunate and became "orthodox learning," it is understandable that he was forced to leave his estate and die as a guest there because of the Shogunate's censure of his life. He was a thinker and communicator who did not tolerate any form of discrimination. =(continued in Part 2) (Kotaro Nagasawa, Director, Platinum Plan Network)