Tokyo's "Miracle Forest" Preserved by Gunpowder and Imperial History: The Ancient Trees of the Institute for Nature Study

Updated by Kazuo Watanabe on January 27, 2026, 9:47 PM JST

Kazuo WATANABE

As a forest instructor, he spreads knowledge about trees and explains the natural environment, and teaches at NHK Culture Center, Mainichi Culture Center, Yomiuri Culture, NHK Gakuen, and others. He is the author of "Trees in Parks and Shrines," "15 Mysteries to Enjoy Roadside Trees," "Why Do Hydrangeas Collect Aluminum Poison in Their Leaves? Completed the graduate course at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Doctor of Agriculture.

Perhaps the deepest forest in central Tokyo is that of the Nature Education Garden. The Nature Education Park is located in Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo, about a 10-minute walk east on Meguro Street from Meguro Station on the Yamanote Line. The park is affiliated with the National Museum of Nature and Science, where nature-related research and education are conducted, but it is also open to the general public, allowing visitors to enjoy the natural beauty of the forest that has miraculously remained in the city.

The Nature Education Park is rich in nature, but at the same time, various people have lived in the park since long ago, and relics that tell the story of the park's history still remain. The park has a trail that leads visitors around the park in about 30 minutes. As soon as you start walking from the entrance, you will see a bank on the east side (right side) of the path. In fact, the bank is an earthwork built in the Middle Ages. In the Middle Ages, there was a castle of a powerful family called "Shiroganechoja" on this land, and the site was surrounded by earthen mounds. The earthen mounds still remain today, reminding us of the past. The earthen mounds were three kilometers long and are said to have protected the castle, which at the time was one of the largest medieval castle buildings in the Kanto region. It is said that there was an empty moat outside the earthen mounds.

As time went by, in the Edo period (1603-1867), it became a suburban residence of the Takamatsu clan in Shikoku. It is estimated that at that time, there was a small pond called Hyotan-ike and a small cloister-style garden. Today, a large pine tree called "Monogatari-no-matsu" (Photo 1) and an old maple tree remain as a remnant of the garden of the Edo period residence.

Also prominent as trees planted in the Edo period are dozens of large sudajii trees. The sudajii is an evergreen tree that grows so many thick leaves that it darkens the area under the tree. The sudajii trees can be seen scattered on the earthen mounds surrounding the site (Photo 2).

These old sudajii trees are thought to have been planted during the Horeki era (1751-1764) of the Edo period. One of the reasons why so many sudajii were planted during the Horeki era may have been to prevent fires. In Edo, fires were so common that "fire and fighting were the flower of Edo. The town of Edo, with its dense concentration of wooden houses, was destined to have major fires. A major fire occurred about once every few years.

It has been known empirically since the Edo period that trees have fire-protective properties. However, the ability of trees to withstand fire varies from species to species. Coniferous trees such as pine and cedar are highly flammable due to the high content of resin (fat) in their trunks, and have low fire-resistance capabilities. Deciduous trees such as konara (Quercus serrata), which are common in so-called "thickets," are deciduous in winter, which reduces their fire-resistance capability. On the other hand, evergreen trees such as sudajii (Castanopsis cuspidata) produce large amounts of moisture-rich leaves throughout the year. These trees are suitable as fireproof trees. The Takamatsu Clan may have planted rows of sudajii trees on their earthen mounds for fire protection.

In the Meiji era (1868-1912), the Takamatsu Clan's premises were also surrendered to the Meiji government. In the first year of Meiji, the site came to be used as a naval (later army) gunpowder depot, known as the "Platinum Gunpowder Depot.

The gunpowder depots were dispersed throughout the site and strictly controlled. Entry by the general public, including residents of the surrounding area, was prohibited. Therefore, although some trees were cut down for the construction of the powder magazine, a considerable amount of wooded area was left uncut. Because of its use as a gunpowder depot, the nature of the area was relatively protected for about 40 years from the beginning of the Meiji period.

Later, in the Taisho era (1912-1926), its days as a gunpowder depot came to an end and it became imperial land (Shirokane Imperial Estate). Although there were no longer any fears of large-scale development, as the Pacific War intensified, the Imperial Estate was increasingly devastated. As the war situation worsened, many air-raid shelters were dug into the slopes, flat land was turned into fields, and wetlands were converted into rice paddies. Trees in the forested areas were also cut down. The Pacific War ended in 1945.

After the war, this land came under the direct control of the national government. However, the issue of which ministry should have jurisdiction over the former Shirogane Imperial Estate was a source of controversy. The Ministry of Construction, which considered it an "urban park," and the Ministry of Education, which considered it a "place for nature conservation, research, and education," insisted that it be placed under their jurisdiction. Depending on the ministry that has jurisdiction over the park, the park may be a park rich in nature or a park with sports facilities or a zoo, and so on, and its appearance may be completely different. In the end, the Ministry of Education decided to place the park under its jurisdiction, based on the opinions of natural science societies, teachers, local residents, and others. Public opinion was concerned about the destruction of nature and disturbance of public morals that would result from the creation of a park, and most people seemed to agree that it should be used as a place for nature conservation and education.

In 1949, the Council for the Management of the Former Imperial Gardens, chaired by then Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, decided to protect the former Shirokane Imperial Estate as a nature education park and open it to the public. For more than 75 years since then, the deep forest in the heart of Tokyo has been protected.

The park's nature education garden offers a varied terrain of plateaus and valleys. On the plateaus and slopes, deciduous trees such as konara and zelkova, and evergreen trees such as sudajii and shirakashi spread out, and in the valleys carved into the plateaus, streams flow, ponds and wetlands are spread out, and wet plants can be observed (Photo 3). Visitors can enjoy nature in all four seasons, including maple leaves in the fall and cherry blossoms and fresh greenery in the spring. It is also interesting to note that the plants that make up the forest have changed over the years, as some plants, such as blue-green algae and Japanese knotweed, have increased in number through the dispersal of seeds by birds.

The park is set up so that visitors can enjoy the nature and history of the area, and interpretive boards are provided to explain the nature and history of the area. It is truly a blessing to be able to enjoy nature and history while taking a stroll in the very heart of Tokyo. It is almost a miracle that an oasis of greenery remains in a metropolis, but it is also a pleasure to stroll through the park and think about the history that created this miracle. (Kazuo Watanabe, forest instructor)

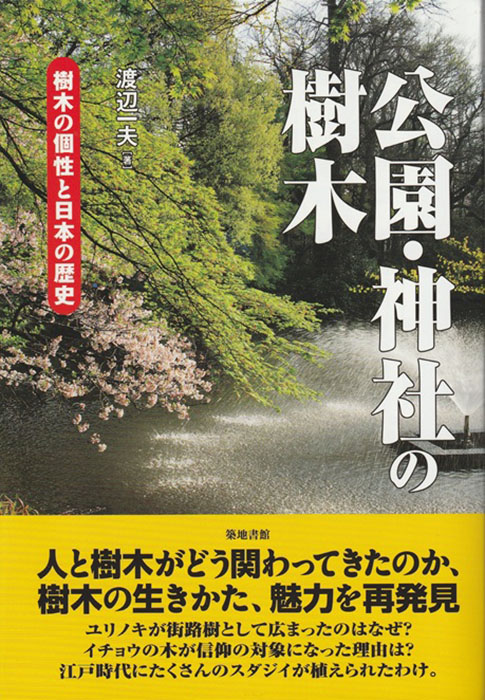

Trees in parks and shrines"

Written by Kazuo Watanabe, published by Tsukiji Shokan

An oasis of greenery loved by people, this book introduces the history and episodes hidden in this oasis of greenery. Through the trees in parks and shrines, this book will rediscover how people have been involved with trees, the way trees live, and their charms.

<Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Sleepless Platanus

Chapter 2: War-Torn Azaleas and Dogwoods

Chapter 3: Enoki, the History of Suigo

Chapter 4: Sudajii fought the Great Fire of Edo

Chapter 5 Camphor Tree from Taiwan

Chapter 6: Why did Eiichi Shibusawa build the park?

Chapter 7: How Ginkgo Came to Be Worshipped

Chapter 8: 5,000 Years of History Hidden in the Cherry Hill