The growing need for foresters with a wide-area perspective and the development of more sophisticated systems in Japan, where the population is declining, is growing

Updated by Takanobu Aikawa on August 15, 2025, 9:54 PM JST

Takanobu AIKAWA

PwC Consulting Godo Kaisha

Senior Manager, PwC Intelligence, PwC Consulting LLC / With a background in forest ecology and policy studies, he has been extensively engaged in research and consulting for the forestry and forestry sectors for the Forestry Agency and local governments. In particular, he contributed to the establishment of human resource development programs and qualification systems in the forestry sector in Japan, based on comparisons with developed countries in Europe and the United States. In the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, engaged in surveys and research for the introduction of renewable energy, particularly biomass energy; participated in the formulation of sustainability standards for biomass fuels under the FIT system; since July 2024, in his current position, leads overall sustainability activities with a focus on climate change. He holds a master's degree in forest ecology from the Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, and a doctorate in forest policy from the Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Hokkaido University.

The starting point of the "circular forest economy" is forest management and forestry operations. How to develop and secure the leaders of this industry is as important an issue as for any other industry. In particular, forest management is important for national land conservation in these days of frequent landslides and forest fires caused by heavy rains due to climate change, and forestry personnel can be positioned as essential workers for the region. In particular, the role of "forester," an engineer who manages forests from a broad perspective, is particularly important. In order to manage Japan's vast forests with a limited number of people, there is an urgent need to develop highly skilled human resources who can use ICT, AI, and other technologies.

The biggest difference between agriculture and forestry is the separation of land ownership from management and operations. Agricultural cooperatives are groups of farmers, and farmers who own farmland conduct their own farming operations. In the case of forestry, on the other hand, many forest owners simply own their forests (although there used to be some who did their own afforestation work), and in most cases the actual forestry work is outsourced to forestry cooperatives or outside contractors.

In addition, given the long-term and wide-area nature of forest management and operations, as well as the increasingly sophisticated social demands for disaster protection and biodiversity conservation, it is effective to deploy "foresters," technicians who specialize in forest management, to manage forests from a wide-area perspective. In many countries, foresters are attached to government agencies and provide advice to forest owners as well as enforce laws and regulations related to forest management and forestry operations. While this is the standard in Europe and the United States, it has not yet been established as a social system in Japan.

It was in 2009, during the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) administration, that an attempt was made to establish a system for forest management in Japan, starting with the training of foresters and their activities, as in the U.S. and Europe. In December of the same year, the Forestry Agency announced its Forest and Forestry Revitalization Plan, which set such goals as achieving a self-sufficiency ratio of 50% in lumber. To achieve this goal, various reforms were to be undertaken, including the development of human resources such as foresters, and the author participated as a member of the study committee.

The consideration was Japan's unique administrative system of forestry and forestry, in which various authorities are vested in municipalities. For example, zoning and forest handling, which affect the harvesting period of forests, are defined by municipal forest development plans.

However, many municipalities do not have forestry specialists, and it is not uncommon to find that employees who were in charge of welfare or taxation are suddenly put in charge of forestry. In many cases, the forestry section is a part of the Agriculture and Forestry Division, which is also responsible for deer and other wildlife, making it difficult to acquire expertise in a few years. Nevertheless, this system has taken root in line with the trend toward decentralization that began in the 1990s.

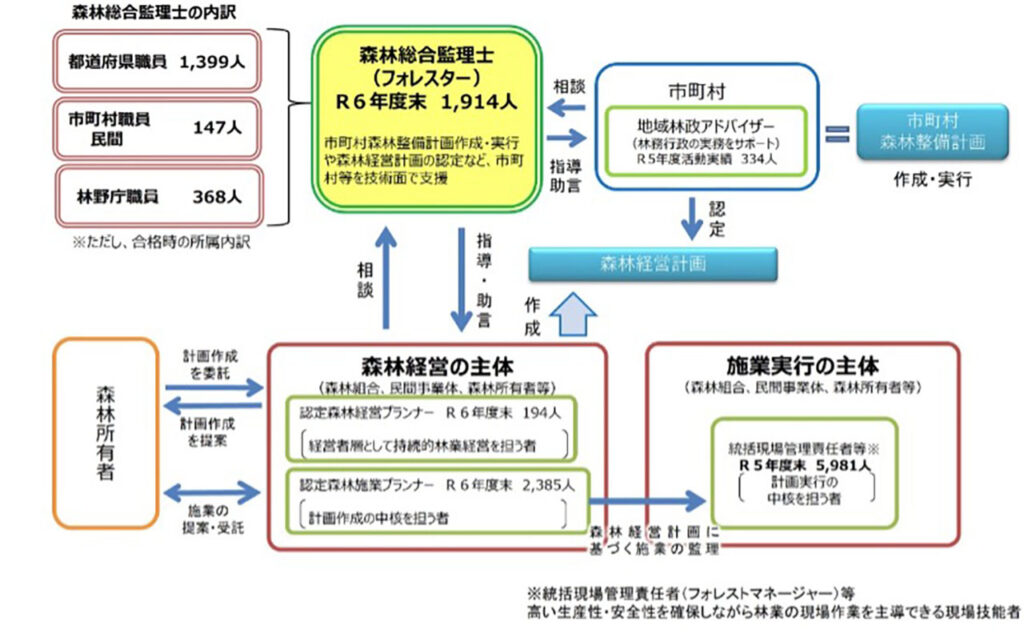

Against this backdrop, the "Japanese Forester," which was established as a division of the Forestry Extension Supervisor category, was given the primary task of assisting municipalities (see figure).

The author himself was involved in the design of the forest general supervisor system and accepts the results. Since then, the Forestry Agency's policies have been designed with municipalities assumed to be the bearers, as symbolized by the Forest Management Control System. On the other hand, it is also important to recognize that the role of "forester" in the global sense is not limited to supporting municipalities. In addition, ten years have since passed, and the following matters may need to be taken into consideration.

One is population decline. This was known even when the Forest and Forestry Revitalization Plan was under consideration, but the issue of "disappearing municipalities" was raised in 2014, which triggered widespread discussion and became a policy for regional development. In the forestry sector, an increasing number of regions are using the Regional Development Cooperative Program to attract human resources from outside the region, some of whom are taking on a forester role.

Second, while the number of civil servants is also decreasing, the budget is increasing. While the general budget for forestry administration has been on a declining trend but has remained in the 300 billion yen range, supplementary budgets have been the norm since FY2009, with an average of 132.6 billion yen over the last three years from FY2022 to FY2024. Additionally, the forest environment concession tax, which began in FY 2019, has been transferred to prefectures and municipalities in the amount of 60 billion yen annually since FY 2024. Given these factors, it is clear that the administrative staff's workload is increasing.

Third is the diversification of social demands. As already mentioned, every year there is a landslide caused by torrential rains somewhere in Japan, and in 2024 and 2025, large-scale forest fires, which had not been common in Japan until now, occurred in many areas, taking people by surprise. In addition, while more attention is being paid to the conservation of biodiversity, damage caused by birds and animals such as deer and bears is becoming more serious, and comprehensive measures are required.

And fourth is the evolution of technology. As in other industries, it is necessary to be proactive in using it, rather than relying on it in the face of a dwindling human resource base. In the author's view, although there have been some attempts to use ICT and drones in forest management, they have not been systematized. Discussions on the use of AI have only just begun.

In the face of these changes, there is a need to train foresters who, in addition to traditional forestry management, also take into account landscape-level perspectives such as biodiversity conservation and disaster preparedness. To this end, a systematic educational system for training foresters is needed, but the practical education provided by the forestry department of the Faculty of Agriculture, mainly at regional national universities, is becoming unsustainable as a framework for such education.

The key to turning things around is to go beyond the framework of "Japanese-style" forester (forestry supervisor) and see if we can train professionals who can compete on a global scale. In fact, there are few schools in the Asian region that can produce such professionals. If even one such professional school were to be established in Japan, the landscape would change considerably. Recurrent education for active forester is also essential.

Another, more fundamental problem is the lack of a larger vision of how AI, in addition to ICT, can be applied to forest management and forestry operations. In this sense, it is certain that how to utilize advanced foresters will also depend on the system. (Takanobu Aikawa, Senior Manager, PwC Intelligence, PwC Consulting, LLC)

*References

Aikawa, Takanobu and Hiroaki Kakizawa (2015), "The Current State of Forester Training and Qualification Systems in Developed Countries and Directions for Change in Recent YearsForestry Economics Research Vol. 61(1), p. 96-107.

Aikawa, Takanobu (2010) "Exploring the Laws of Advanced Forestry Management for the Growth of Japan's Forest IndustryNational Forestry Extension Association.

Kazuhiko Toyama (2024), "White Collar Disappearance: How We Should Change the Way We Work" (NHK Publishing Shinsho)