Timber supply chain management as seen through the rice riots and wood shock

Updated by Takanobu Aikawa on September 16, 2025, 6:17 PM JST

Takanobu AIKAWA

PwC Consulting Godo Kaisha

Senior Manager, PwC Intelligence, PwC Consulting LLC / With a background in forest ecology and policy studies, he has been extensively engaged in research and consulting for the forestry and forestry sectors for the Forestry Agency and local governments. In particular, he contributed to the establishment of human resource development programs and qualification systems in the forestry sector in Japan, based on comparisons with developed countries in Europe and the United States. In the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, engaged in surveys and research for the introduction of renewable energy, particularly biomass energy; participated in the formulation of sustainability standards for biomass fuels under the FIT system; since July 2024, in his current position, leads overall sustainability activities with a focus on climate change. He holds a master's degree in forest ecology from the Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, and a doctorate in forest policy from the Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Hokkaido University.

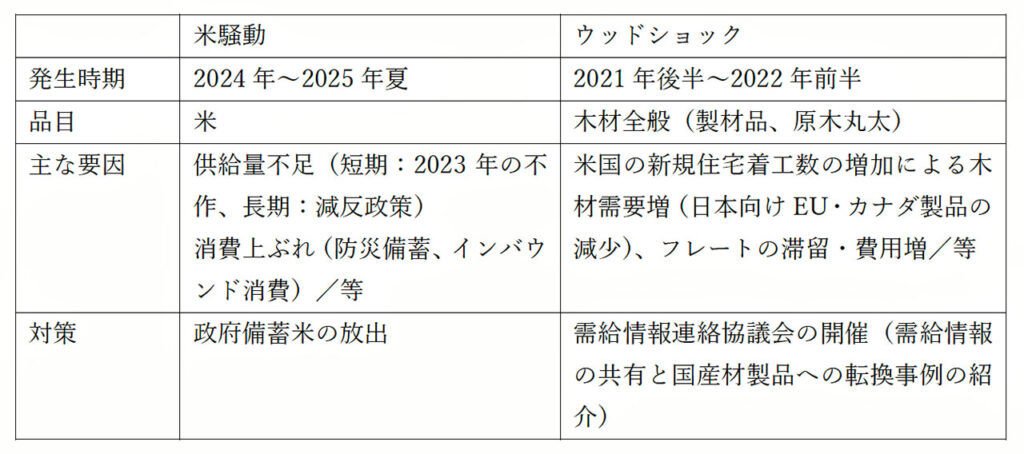

From 2024 to 2025, a rice shortage occurred and rice prices soared nationwide, resulting in the so-called "2024 rice riots". Meanwhile, in the forestry and timber industries, a shortage of imported timber and rising prices in 2021 will lead to a shortage of timber, including domestic timber, and soaring prices, resulting in a "wood shock. In aiming to realize a "circular forest economy" in the future, we must take this reflection into account and build a reliable supply chain that can respond to new demand for chemicals and other products.

At first glance, the rice riots and the wood shock are very similar matters, but in fact there are differences in many respects. The most significant difference is that while domestically produced rice accounts for the majority of rice, imported timber dominates the supply of lumber, even though the self-sufficiency rate has risen to 40%. Therefore, while the cause of the rice riots can be mainly attributed to the insufficient supply of domestically produced rice, in the case of the wood shock, it was the insufficient supply of imported lumber and its soaring prices.

Therefore, with regard to rice, in addition to the fact that the situation was brought under control through the active measure of releasing government stockpiled rice, a scalpel was also brought to bear on the state of its distribution and production system. As for new uses for rice, such as feed rice, the inducement of rice exports through subsidies under the policy of reducing rice acreage was considered a problem, but it was determined that export rice was "not the cause of the rice riots" and that active measures would be taken in the future.

Wood shock, on the other hand, sawmill and laminated wood prices soared up to 2.5 times in late 2021 and early 2022. Prices then naturally declined, and by 2023 were seen as "converging," although prices remained at higher levels than before the Wood Shock.

The Forestry Agency also held a liaison conference on supply and demand information during this period, sharing information on supply and demand and introducing examples of conversion to domestic wood products, among other measures. However, as a result of the spontaneous convergence of the wood shock in a sense, it appears that the factors that led to the shock have not been summarized and lessons learned have not been shared. In the 2021 edition of the White Paper on Forests and Forestry, there was a special feature titled "Response to the Lumber Shortage and Price Increase in 2021 (So-called Wood Shock)," but in the subsequent 2022 edition, although there is an explanation of the increase in lumber prices, the phrase "wood shock" is no longer used.

No one knows, of course, whether Wood shock will occur again in the future. In fact, however, the current Wood Shock is regarded as the "third round," and similar situations have been repeated in the past. The first one was triggered in 1990 by the U.S. regulation of logging in national forests, and the second one was triggered in 2006 by Indonesia's illegal logging measures and Russia's increase in log export tariffs (Tachibana 2022).

It is noteworthy, however, that especially after the second wood shock, when the yen was weakening and the euro was appreciating, and the prices of European lumber products such as lumber plywood and lamina were rising, an ambitious policy was launched to drastically change the supply structure of domestic lumber. Specifically, the Forestry Agency's "New Production System" project was launched in 2006, bringing about the current trend toward larger domestic lumber mills. It was also around this time that the Forestry Agency launched its "Proposed Intensive Management System" (since 2007) and the "Forest Management Planning System" (since 2012).

While the new production system has been praised as revolutionary in that it provided subsidies to private sawmills to expand their scale, the key point was the reform of the distribution system, particularly the log market. The log market has played a major role in the distribution of domestic lumber. It was as if we went to a supermarket to buy ingredients for dinner, and the market would be ready and waiting for us when we needed it. It is said that it was also common for some people to use the log market's dirt floor as a warehouse and leave logs there without taking them back.

However, as lumber mills become larger and more systematic in their production, it is more convenient for them to make direct deliveries without going through the market. This is the same way that restaurant chains, let alone local restaurants, do not go to supermarkets to purchase their products. The new production system was the result of a scalpel that was applied to this problem, and new distribution methods were spread throughout the country, such as direct delivery from the mountain soil or intermediate soil to lumber mills, or fixed-lot sales based on prior agreements, even if through the log market.

However, after this third wood shock, no policy seems to have been made to significantly change the supply and distribution system of domestic lumber. In such a situation, a hint of future developments can be found in the experience of the Wood Shock.

During the wood shock, sawmills and laminated wood mills tried to make up for the shortage of imported lumber by releasing product inventories. However, efforts to increase the supply of domestic logs, the raw material, appear to have been limited. However, a paper analyzing the Tohoku region's response to the wood shock (Otsuka 2023) reported that "for forestry operations with ample standing timber inventory, the inventory they had already purchased enabled them to adjust production while earning more profit.

Inventory" in the form of standing trees is the most reasonable. Of course, considering the risk of disasters and the appropriate diameter, the trees cannot be left there forever, but the management costs are close to zero, and the trees grow and become larger as they are left there. Ultimately, if a road network is in place, it is not impossible to operate on a just-in-time basis, with logging, lumbering, removal, and shipping the day after an order is placed.

Thus, having standing tree inventory in addition to product inventory may contribute to supply chain stability. The assumption is that supply and demand information is shared among owners of standing timber (Shioji et al. 2022). To begin with, however, it is difficult to say that supply and demand information is sufficiently shared in the current timber supply chain. For most forest owners, the timber market has changed dramatically since they planted their seedlings 40-50 years ago, and harvesting a stand is a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Therefore, it is realistic for forestry entities to hold standing timber as inventory in advance, but the intervention of a forester who stands by the forest owner's side and provides advice can maximize the forest owner's profit. Discussions are needed to use the wood shock as a springboard to the future. (Takanobu Aikawa, Senior Manager, PwC Intelligence, PwC Consulting LLC)

■References

Tachibana, Satoshi (2022) "Why Did Wood Shock Happen? ~Implications from Overseas Dependence to Domestic Resource Use", in "Forest Environment 2022" edited by Forest Environment Study Group, Forest Culture Association, Japan.

Hirofumi Shioji, Eri Bunzuki, Hiroto Takaguchi, Akira Matsumoto, Hideo Sakai, Yukio Teraoka (2022) "Forest Islands Regeneration Theory: Innovation 'Forest Link Management' Linking Forest and Architecture" (Nikkei BP)

Otsuka, Ikumi (2023), "Wood Shock and Forestry Productivity in Northern Tohoku Region" Forestry Economic Research Vol.69 No.1 pp16-26.